Behind The Scenes With Nick Cave: The Making Of 20,000 Days On Earth (Interview)

The New Zealand International Film Festival is just around the corner and The 13th Floor is planning to give the event extensive coverage. The festival always manages to present a selection of formidable music films and this year is no exception. At the top of any music fan’s list should be 20,000 Days On Earth, a film about Nick Cave. More than a typical rock doc, this stunning film digs deep into the creative process while also presenting Cave in unique situations with many of his collaborators past and present such as Warren Ellis, Blixa Bargeld and Kylie Minogue. The 13th Floor’s Marty Duda recently spoke to Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard, the directors of 20,000 Days On Earth. Forsyth and Pollard have been working with Cave on and off for years and have just won the Best Directing Award at this year’s Sundance Film Festival.

Click here to listen to the interview with Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard:

Or, read a transcription of the interview here:

MD: Your film is playing at the New Zealand Film Festival at the end of July and I’ve had a chance to see it beforehand and I must say I was very impressed. I’m a big Nick Cave fan so I was excited to see it. I came into it, you know, being a wary because the only thing that I really knew about your film making was the series of films you made for the Nick Cave reissues, the Do You Love Me Like I Love You series, so I was wondering if it’s gonna be all talking heads cut together or what you had in mind. I came away very impressed with what I saw.

JP: Well it’s not like, you know, we made those…that series of films were made for the fans. They were made to be watched on your T.V, in your DVD player at home, you know, and really only by those die hard kind of fans where an album means so much to them that they really wanna know what it means to other people and, you know, they were a very narrow kind of audience.

MD: Right, right.

JP: So we knew, you know, we knew that they were made for those people in mind and we count ourselves as those people.They are these albums that mean an incredible amount to us and in our relationship. When it came to the film, we wanted to do something really different really, we wanted to make a music film like you’ve never seen before and, you know, one that didn’t have to be… so many good music films are only good because they come out of struggle. You know, I’m thinking of The Devil And Daniel Johnston, I’m thinking Dig!, brilliant, brilliant films but films that are built on struggle and jeopardy and misfortune. We wanted to make a film about somebody at the height of his career, at the peak of his ability…is still as progressive as he’ll ever be, working hard than he’s ever worked, you know, is successful and that in filmic terms that’s not an easy story to tell so we really need to get back and start thinking about how to do it differently, How to tap into what is it that makes him just such a remarkable person and what it is about his process that we think could be universally inspiring.

JP: So we knew, you know, we knew that they were made for those people in mind and we count ourselves as those people.They are these albums that mean an incredible amount to us and in our relationship. When it came to the film, we wanted to do something really different really, we wanted to make a music film like you’ve never seen before and, you know, one that didn’t have to be… so many good music films are only good because they come out of struggle. You know, I’m thinking of The Devil And Daniel Johnston, I’m thinking Dig!, brilliant, brilliant films but films that are built on struggle and jeopardy and misfortune. We wanted to make a film about somebody at the height of his career, at the peak of his ability…is still as progressive as he’ll ever be, working hard than he’s ever worked, you know, is successful and that in filmic terms that’s not an easy story to tell so we really need to get back and start thinking about how to do it differently, How to tap into what is it that makes him just such a remarkable person and what it is about his process that we think could be universally inspiring.

MD: Right. The first thing that came to my mind was how did you present the idea to Nick himself because I would imagine that would have been, you know, quite a, I mean you would have had to do it exactly right or he would have just said no I don’t want to have anything to do with this.

IF: I mean it wasn’t, funnily enough it wasn’t a process that really came about like that. There was never kind of a big idea and there was never, kind of, you know, a big pitch. What actually happened was that, we got a call from Nick saying ‘look I’m about to start working on a new record’ and that was the record that we now know is Push The Sky Away and he said ‘look I know you guys well now and I thought it might be nice if you came in and filmed some stuff’. So the pair of us went down to Brighton to see Nick and Warren, where they were writing, and we filmed there for a couple of days and then we went with them to the recording studio and spent, I think about 12 days in total shooting the sessions they were doing there. But at the time we were doing that was not really a kind of plan for what was gonna happen to this material, it was just a kind of through the relationship and through the friendship and trust that we had, Nick kind of figured that he could cope with us being around. So it’s kind of shot in that way and once we had that material and we all began to sit back and look at what had, it kind of seemed obvious to us that we shouldn’t just let this become some kind of, you know, I mean the kind of thing that happens with this sort of material normally, you know, record companies get their hands on it, it goes on YouTube or it goes on, you know, bonus disks and all this kind of thing. We just felt like we had something more interesting, more important and more special than that.

MD: Right.

IF: And so that’s sparked a conversation about what do we do?

MD: And when did the idea present itself to have it as scripted as it is because quite a bit of it is, well the credits are co-writes between you and Nick. So there must have been at some point where that was decided upon and… where did that come from?

JP: Well we started with the title. We borrowed Nick’s notebook, the book he’s been writing, Push The Sky Away, and began to look for the stuff that hadn’t found its way into a song. Just, you know, we knew that it would be the stuff that was in his head at the moment.

MD: Right.

JP: And we found a lot. I mean the opening lines to the film, ‘At the end of the 20th century I cease to be a human being, I write, I eat, I work,’ whatever it is…that line was a discarded lyric and it means we kind of highlight that and we’re like yeah okay, we know we’re gonna use this and maybe this is even our way in, such a good opening line. The title 20,000 Days On Earth was a kind of calculation around a song that Nick had been writing about how many days he’s been on earth and we just love the phrase in it. It seems to speak of bigger things just like what do we do with our time on earth, how do we measure it, you know, what is it that makes us who we are. and we love that. So it was a, I wish I had a better story, but it was a pretty organic process. We then wrote a script, we wrote a script that had absolutely no dialogue in it. So based on the title we decided to use the 20,000th day on Earthas a kind of cinematic structural sort of conceit for the shape of the song, that he’s wake at one end of it and that we’d see him, you know, heading to bed, sailing to sleep at the other end of it.

MD: Right.

JP: There was a, you know, there was a script, all of the scenes were written up be we just had no dialogue at all. And then we, the first thing we did was shoot the psychologist scene. We shot that ahead of principle photography, a couple of months, and we shot ten hours of that with Nick and Darian talking. It was completely improvised. There was no script, no notes, it was a completely improvised conversation in one take. We would never ask Nick or Darian to repeat anything. It happened as a real conversation would. And in fact, that kind of set the theme and set the tone to the whole film. Everything from that point happened in one go. So that the archive scene’s the same, all of the drives are the same, they’re unscripted and they happen in one take. So it’s just a way that we really like to work and certain that we know it works well for Nick because he’s, he’s not a great actor but he’s tremendous at being Nick Cave. He is incredibly honest, very, very open, really kind of, willing to throw himself into a situation and give it a shot and it just seemed to work incredibly well. Nick’s writing came, kind of, a slight step later than that. As we were starting to stitch the scenes together and we had these passages that they, you know, just driving or walking down a, you know, across a garden or whatever, we wanted to bring in some voiceover elements. And some of them we found in the notebooks but we wanted more. So we would email Nick whilst he was out on tour and I’d just give him a subject say ‘oh can you write something about statues, about being forgotten, about the afterlife, about loneliness, about, you know, and we just, we’d give him a topic and then he’d write a paragraph or two and then send it back. And they were amazing! They were just incredible. In fact, one of the first that we got was the passage that you hear when he’s looking in the bathroom mirror and he talks about being a cannibal and that nothing in his relationship with his wife is sacred and it all gets, you know, it all gets churned out. And it was just then we had to, everything galvanised and we could really see that, that we had a kind of formula for making a film work.

MD: It’s interesting that you say that most of the scenes were shot in one take because several of them seem like they are staged because of the way, you must have multiple cameras set up to cover whatever it is that you’re shooting. So it feels like there’s, you know, that there’s quite a bit of thought gone into, you know, setting up the cameras and making sure that you grabbed every shot and that they are almost like set pieces.

IF: Yeah. I remember a huge amount of thought goes into and that’s really why it’s able to work. You know, I mean the purpose of not repeating things and not doing things multiple times is really to ensure that what we’re getting is the very best performance out of Nick. You know, without the, kind of, training and discipline of an actor…you know, I think anyone if you ask them to repeat something, you know, can you say that again, can you say that to the camera, you know, kind of disciplines of film making, you get very, very wooden, very uninteresting material very, very quickly. So the kind of, the idea at the heart really of our approach to making this film was always about creating situations in which the situation itself would be very artificial. So something like the psychiatrist’s office for example, you know, it’s a constructed set, built completely, it’s not a, you know, it’s not a real office but it is a real psychoanalyst.

MD: Right.

IF: Office is set up in a way where the cameras are pretty discrete. So when Nick sits in that chair and talks to Darian, he’s basically having a conversation, one on one, with a psychoanalyst. And of course he’s aware that there’s cameras there, of course he’s aware that we’re making a film but you know, when you film like that after the first, you know, 20 minutes, 30 minutes, people quickly kind of forget the higher purpose and get lost in the moment. We shot for about 10 hours with that scene alone so. Yeah that was our approach.

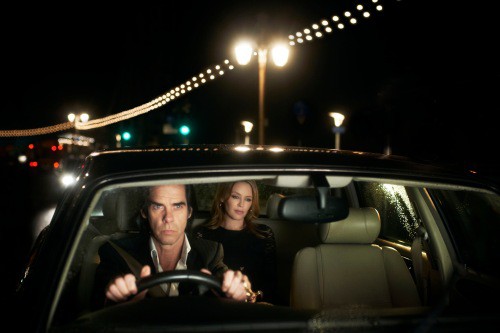

MD: And I guess one of the most memorable series of shots in the film is Nick driving around in his Jaguar and suddenly Ray Winstone and Kylie Minogue and Blixa show up, you know, taking to him. I was especially surprised to see Blixa there because obviously he’s not a Bad Seed anymore. Can you tell me a little bit about how you got Blixa to be involved in it, you know, if there was any kind of tension between them and just technically how you shot that because you seem to have cameras everywhere.

JP: (laughing) We shot it, we were only filming for about 25 minutes. It was… happened really, really quickly. The drives were the most nerve-wracking thing we did because they needed to happen very quick, they happened without a script, without notes and by trying to keep Nick and whoever apart until they got in the car so they wouldn’t, kind of have any discussion that they could have beforehand.

MD: Right.

JP: And we’d seen, we were on tour with Nick when he was doing a set of European shows around the release of his second novel, The Death Of Bunny Munro, and we produced the audiobook for that. And we went out on tour of doing some videos and lights and stuff and Blixa turned up at one of the shows in Germany and read, in German, read a passage from the book. And Nick, you know, they’ve spoken, they’ve emailed, they had been in touch and there is a real fondness between them, but they never talked about why Blixa left the band, not since that first email that came through. And we just thought it would be a really, you know, incredible thing to do. I mean without, you know, Roland Howard around anymore, Blixa is really, is such a crucial part of Nick’s past of that story of the, you know, the way in which Warren is now that sounding board, that real kind of, creative, collaborative, cog in the Bad Seeds. Blixa was that, Blixa was fundamental to Nick’s progression for such a long time, really, that relationship was so both, personally and professionally, such a close one. And it just felt like something would happen. Blixa’s so incredible anyway, he looks brilliant.

MD: He does.

JP: He kind of makes a… he’s thing is kind of being odd and we knew something would happen and we were really pleased when that drive went well and they managed to find a way to kind of navigate that moment,

that kind of conversation, which we’d not sort of said beforehand that. We talked briefly to Nick about it, said ‘do you reckon we, you know, would you talk to him about it’ and Nick was like ‘I dunno, we’ll see, I dunno’, but we didn’t talk to Blixa about it at all so.

MD: And was there any effort to include Mick Harvey into the film at all? You speak about guys who have kind of gone back with Nick to the Birthday party and whatever. He’s kind of obvious by his absence I guess.

JP: Yeah but he’s only recently kinda out, you know. He left such a little time ago that I don’t think that there’s a context for that relationship yet. I don’t think they kind of resolved that and then while their connection was such a, I mean so long standing, clearly so absolutely, hugely fundamental to the progression of the Bad Seeds into their, their ability to even carry on at times. But, you know, it’s early days, its early days for them to kind of find a way to talk to each other and certainly. I mean that was our call, we didn’t see, we didn’t feel that there would be anything revealing or substantial to kind of, to come out of that. You know, we only had 97 minutes and we chose to tie ourselves to the biography and to the truth…

IF: Yeah. I mean I think that’s also it, isn’t It. It’s just, you know, with any kind of situation like that, there’s a lot of complexity, politics and we were very, very determined for the film to not get caught up in that kind of…you know, there’s a lot of people that have touched Nick’s life over the years and, you know, you could probably imagine people have asked questions about, you know, why is Polly Harvey not in the film, there’s another one.

MD: Right.

IF: Certain people feel, you know, perhaps she would have been an interesting voice with her in film. I think for us, the voices that are there are the ones that we thought could bring something interesting to Nick and to the elicit something interesting from Nick for the film.

JP: Yeah. Within the themes of the film, you know, they fit really well. He’d just come out of being with Warren. It’s really natural that he’s thinking about collaboration and collaboration, you know, the collaboration with Blixa was a remarkable one. I mean it had a…remarkable in the same way that I think that he has with Warren now, that spark, that real kind of a, that they both mean something so musically kind of off kilter and peculiar to the Bad Seeds. And he had just been looking at the photographs that are in the archives so again as storytellers as kind of film makers, we could find a way, a web, a way of weaving that into our kind of timeline.

MD: Right. Now the film also contains some absolutely stunning, what seems like, concert footage of Nick and the Bad Seeds performing Jubilee Street. Is that staged or was that an actual show? Again you seem to have cameras everywhere in the right places capturing this amazing moment, you know, with Nick interacting with the audience.

JP: You’re making us sound like superstar directors who know what they’re doing.

MD: Well it looks that way.

JP: It was a real show, it was the first time they’d ever performed at the Sydney Opera House and it was an amazing show. We were really lucky to be able to film that. We had about 8 cameras there and had to be very aware of not getting in between the audience and the band so we didn’t spoil anybody’s experience. And that meant a lot of our cameras were off on the side of the stage. So we got some great footage. For me the real turning the point in the film was when we started to layer… was seeing that performance and then finding that we can start to splice in old performances and find moments from past performances where you are almost in the same position on another stage, doing the same kind of move and it just suddenly felt like there was something really kind of exciting about that…that the past kinda began to haunt the present and it was, it kinda got your heart racing. You know, even as we were editing it, you could really feel, you got a real sense, of what it was gonna do in the cinema.

MD: Yeah and I guess, coming, the thing that I came away from the film at the end of it, the biggest thing was the feeling that, you know, you understood that Nick Cave was an artist who, you know, had chosen this particular thing to do, this music and to a certain extent his writing as a career move as something that he wanted to have a legacy with, whereas, you know, there are a lot of musicians who are just, you know, forming a band to meet girls or do whatever it is that they do, you know, in their 20s and that’s about it. With Nick Cave that, and there are obviously other artists like that, it was a bigger thing than that. Was that what you guys came away with, with him?

JP: I think it, it leaves me? We wanted to leave people feeling that sense of, well feeling what we know when you get to know him which is, he’s just really inspiring. Not in the kind of ethereal, wishy washy,’Oh, if only I was as good as him’ way. You know, really meaningful actual, kind of kick up the block type of a way, where he makes you think, ‘I must be better, I must try harder, I must do more, I should pick up that pen, write that novel, paint that painting,’ whatever it is. He just makes you feel like it’s a buyable option…that seeing through a small idea and just bothering to kinda run with it is manageable, is achievable. For somebody so utterly extraordinary to leave you feeling that level of creativity or that access into it is achievable and acceptable is that I think Is really incredible.

MD: Yeah. Now just kind of to turn the conversation around about yourselves. How do the two of you work together when you’re putting a film like this together, do you have specific roles that you assign to each other? You’ve been working together for quite a while, how has that developed?

IF: Yeah, I mean we’ve been working together since we met at art school so 20, 20 something years now. It’s been such a long time that it is honestly something that just doesn’t really, doesn’t really need any thinking about anymore. I guess it just kind of, it kind of works. We certainly don’t have particularly delineated roles, it’s not a kind of, you know, Jane does the production and I do the whatever, it’s a much more fluid thing than that.

JP: I’m a lot louder!

MD: Alright. Does that help?

JP: Yeah, sometimes it’s needed. And you know, it doesn’t get any easier, you know, it’s not a…I mean I think I’m very lucky that I found the person that I want to be with and that inspires me and that I still am excited about, you know, and scared about what’s coming next but still quite trilled. But it doesn’t mean that we don’t argue.

MD: Right.

JP: We argue all the time. You know, yeah it’s a struggle. And working that closely with anybody is gonna be, you know, a bit of a nightmare some of the time and, but yeah we just, you know, you just share it and sometimes it works and you find your rhythm and your routine and sometimes it’s hell. It seems to have worked on the film alright.

JP: We argue all the time. You know, yeah it’s a struggle. And working that closely with anybody is gonna be, you know, a bit of a nightmare some of the time and, but yeah we just, you know, you just share it and sometimes it works and you find your rhythm and your routine and sometimes it’s hell. It seems to have worked on the film alright.

MD: And are there future projects? Are you in the process of working on something new now?

JP: Yeah, yeah. Oh this has really given us an appetite for film. I think that, you know, we’d always the kind of boundless parameters of art, that really anything goes. But unfortunately I think that art has kind of dug itself into a little hole in contemporary culture, that means that an audience really doesn’t stand much more than a minute or two with it. And that’s kind of affected the making, you know, you’re trying to get across an emotion or an idea or an experience but you having to do it in a really sort of short amount of time because people’s patience with contemporary art is…understandably, you know, because of a lot of rubbish that’s in there… it’s fairly thin. And the one great thing about moving into film or television is that people are willing to give it more time. That, you know, you invest like 90 minutes and go and see something on a big screen or you’ll get your feet up on your sofa and knock the DVD in and give it a chance. And being given a chance as the maker, the person at the other end means you can, you now…there’s so much more scope for what you can do. You can join ideas together, you can call back, you can weave things through. I mean I think the film kind of hopefully sounds testament to just how excited we got about getting more than just a couple of minutes of somebody’s time and how we really wanted to cram everything into it, and make it a worthwhile experience for people watching.

MD: I assume you must have had some kind of screening for Nick and the band members and people who were involved in the film. What was their initial reaction when they saw the finished product?

JP: Yeah we watched… I mean Nick saw the first kind of main cut of it. He didn’t see anything while we were editing till we got to a place where we thought we had, you know, close to a finished thing and then he watched it. And that was a really nerve-wracking 90 minutes, 100 minutes. It was crazy, you know, waiting to hear whether kind of what he thought was gonna come out of all of those days of filming and all of those discussions about ambition and intention, whether your thing and his thing aligned in some way or whether he respected what you had done. And it was great when he turned around and held up a blank notepad and said, ‘nothing, sorry’.

MD: I get the feeling that if he did have issues, he’d probably let you know about them I assume.

JP: I hope so. We got to watch it finished together at Sundance. When we took it to Sundance, we’d only finished the film 9 days before that and so it was really, you know, it was really kind of, the paint was still wet, it was very early days and incredibly exciting to watch it together with, you know, with all the people there.

MD: And you won the directing award at Sundance right?

JP: Yeah.

MD: And I believe you also, Jonathan Amos won for his editing work as well. Is that correct?

JP: Yeah.

IF: Yeah, that’s right.

MD: And there’s some amazing editing involved with that film. I can think of scenes where, you know, Nick was reading aloud and there were a bank of monitors that were kind of revealing footage that reflected what he was talking about at the time. Maybe you can talk to me just a little bit about the editing process.

JP: Yeah, John’s a brilliant editor. It took us a while to find the right person to work with. We met some amazing documentary editors, some amazing film editors, but we just weren’t clicking, you know, it was, and I think was it was in hindsight I think it wasn’t until we found it that we knew what we were really looking for. We were looking for somebody that shared our sense of humour and therefore we shared the same sense of humour as Nick and Warren and the band and kinda get it because their funny and we knew the film needed… because the film was going to get, you know, at times not pretentious, but big in its thinking, you know, it’s gonna proclaim some fairly bold kind of artistic ideas and ideals but at the other end of that you got to be able to make somebody giggle and, you know, you’re only gonna get away with one if you can do the other and John was, you know, the first person that we met, that we could see that with, we could understand that we could be having a conversation about a kind of theoretical message or serious side but also be kind of laughing about the fart jokes.

MD: Right.

JP: You know, kind of getting the funny stuff in there and yeah he was great. It was a really good relationship, one that I think we look to kind of, he’s someone we’d like to work with again.

MD: Now I’m gonna be going to The States at the end of July, I’m going to New Orleans and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds are gonna be playing there and when I was kind of researching getting tickets for the show and all that. I read, believe that the film is being toured along with the band in The States are they kind of taking it around and having screenings as they’re touring. Is that right?

JP: Yeah. They’re doing like special events screenings.

IF: Our distributor in the States, Drafthouse, are really great and they have a real kind of history of, that they grew out of a chain of cinemas. So they own cinemas and they kinda really get the importance of the experience of seeing movies in cinemas. So they’re fantastic and yeah because Nick is currently strutting his way across The States, they set up this series of kind of special preview screenings ahead of the release in September.

MD: Right.

IF: and I don’t think it’s all, but most of the towns that Nick’s playing in, there will be a screening kind of on the day or the day before, something like that, so people can get a chance to see the film and the band live around the same time.

MD: Yeah that’s pretty cool.

IF: Which is great.

MD: Yeah. I believe he’s coming here to New Zealand to do solo shows in December so that’s even more interesting.

JP: Yeah, that’s right?

MD: Are you planning on working with him at all again in the future or you kinda gonna go off and find something else to do?

JP: I’m sure we’ll work together again. Yeah I’m sure. I mean we’ve worked pretty, we’ve worked on stuff regularly over the last 7 years, I can’t see that stopping. We all seem happy with each other and the film hasn’t changed that which is great.

MD: Yeah.

JP: I would imagine there’d be more stuff yeah.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0tIH2P-6cZ4]

- MY BABY ANNOUNCES 2025 ACOUSTIC BLUES CLUB TOUR OF NEW ZEALAND - December 11, 2024

- Train Announces Auckland Show For 2025 - December 9, 2024

- JACK WHITE: 2nd & FINAL SHOW added at Auckland’s Powerstation - December 6, 2024