Director Sophie Fiennes on Making Her Grace Jones Documentary: Bloodlight And Bami

English film director Sophie Fiennes comes from a family of artists. Her brothers, Joseph and Ralph, are both acclaimed actors, while her mother, Martha, is a director and her father, Magnus, is a composer.

Sophie began making her own films in 1998 and her most recent is a rather surprising look at musical icon Grace Jones, titled Bloodlight And Bami.

Rather than making a traditional retrospective film about Jones’ career, Fiennes and her camera have followed Grace as she performs, meets with family members and wheels and deals on her phone from various hotel rooms. It’s an intimate fly-on-the-wall look at one of music’s most mysterious artists.

The 13th Floor’s Marty Duda spoke to Sophie Fiennes just ahead of her film’s limited release in New Zealand cinemas beginning March 8th. Of course Grace Jones herself will be performing in New Zealand later this week…Friday, March 2nd at Queenstown Events Centre and the following day at Auckland City Limits Festival at Western Springs.

Click here to listen to the interview with Sophie Fiennes:

Or, read a transcription of the interview here:

MD: I, first, just wanted to get some background on how you came to the idea of doing this documentary. My understanding is you had done one on Grace Jones’ brother, who is some kind of religious leader, and that led to it.

SF: Yeah. It wasn’t about her brother, really, it was about the church and his sermons; so, in a sense, it was the performance of church if it were used to build a picture of the community, and look at how his sermons connected to the lives of the people in that community. Grace saw that film, and it was the fact that she came to the screening of that film – the first ever time that I projected that film when it was completed – and we got on immediately; and she really appreciated the film, and the approach of the film, and I think, probably, the visual, cinematic quality of it as a documentary; but it also had a strong visual feel to it that I think she really responded to.

MD: So, was it her idea, or your idea, to do the film about her?

SF: It was actually her idea. She called me about eighteen months after I’d first met her… – because we got on, and we kept a little bit in contact – then she said, “I’ve just had a request to make a film, and to do a documentary; and what they want to do is just not me. It’s just not what I want to do, but why don’t we do something together?” It was very much just a seed of an idea, and just to film and to keep shooting…. We did the red carpet interviews last October, when the film was released in the UK, and she made this lovely comment, “When you conceive a child, you don’t know what it’s going to turn out like.” It’s really a great metaphor for how it was just embarking on an idea, and then seeing what happened. In documentary, you’re not in control of the narrative; you’re just there, free-weaving through what life’s throwing at you. That’s kind of how it started.

SF: It was actually her idea. She called me about eighteen months after I’d first met her… – because we got on, and we kept a little bit in contact – then she said, “I’ve just had a request to make a film, and to do a documentary; and what they want to do is just not me. It’s just not what I want to do, but why don’t we do something together?” It was very much just a seed of an idea, and just to film and to keep shooting…. We did the red carpet interviews last October, when the film was released in the UK, and she made this lovely comment, “When you conceive a child, you don’t know what it’s going to turn out like.” It’s really a great metaphor for how it was just embarking on an idea, and then seeing what happened. In documentary, you’re not in control of the narrative; you’re just there, free-weaving through what life’s throwing at you. That’s kind of how it started.

MD: It’s interesting, because, obviously, it’s a collaborative process between you and her to make this film; whereas, traditionally, the film maker has a vision or an idea, and the subject is simply the subject, who gets shot, and is at the mercy of the film maker. Did it take you any time to get your head around the idea that this was the way that this was going to be, or is this how you prefer to work anyway?

SF: It’s a collaboration, but I never make a film without keeping final cut, and Grace didn’t want to control anything. She’s a very good collaborator; and that doesn’t mean breathing down my neck. In fact, she put huge amount of trust in me, and that brings out the best in you; when someone’s trusting. It wasn’t like we knew what we were going to make, but we just knew we were going to make something together, and she is the subject, and I am the film maker; so, we have our different roles within that collaboration. It’s not like she’s going to start directing the film. She was going to submit to my camera, and that was her decision: to be completely not in control; to be shot without makeup on – she’s controlled her image hugely – but I think that was the challenge she set herself: to allow that to happen, and to not be in control; but to trust that I was a visual film maker, and that I took the time to understand her, and bring all of that knowledge, over time, into how I shape the edit. She never wanted to see or look at footage, or anything.

MD: Oh, really?

SF: No, no. She didn’t want to. It’s as I say: she’s collaborating, but as a subject. I showed her the cut of the film when it was, pretty much, done, to make sure that she could recognise herself in it, and have anything she wants to say – in legal terms, it’s called ‘full and meaningful consultation’. When you get money investment on board, you have to have everything ironed out, legally, as to how things are going to work; and, as I say, I wouldn’t make a film if I didn’t have final cut.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HScUsiZLoCg

MD: Mentioning getting the money together to make the film: I’ve read, where you ran into some issues, there were folks who thought that making a film about Grace Jones, it wasn’t, at least, an archival thing; was something that people just wouldn’t be interested in, and, perhaps, there was some sexism involved in that. Can you explain what the process was like to be able to get this film made?

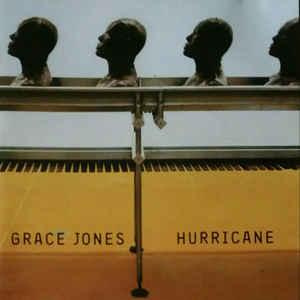

SF: I think that the time at which this film came out was really interesting, because, of course, it hit the theme of these allegations against Harvey Weinstein, and questions about what it means to be a woman in the world; so, that’s been very interesting to track. It’s less to do with being a woman; it’s more to do with the form of films, and the way that documentaries are made: that there’s an assumption about how music documentaries might be. Everything has become themed, in terms of genre, now. When I started being excited by film, I didn’t look at films in terms of genre. I saw creative people: film directors working in teams with cameramen – very collaborative, always, film making – and I saw people who were making films, and they created film, but writers would write novels. Then I’ve seen, increasingly, a huge… change to just want to see through the grid of ‘genre’, which is a very reductive way, but it’s convenient for the market, because they can say, “We’re marketing this as a rom-com. We’re marketing this as a music doc. We can market this as a thriller. We can market this as sci-fi horror.” If you’re coming with something like, for instance, one example: when we were trying to raise the money, they had quite a sizable budget to invest in what they thought were films about icons, and we thought, “Oh, great! This is going to be perfect,” but no, no, no, “This isn’t the kind of icon that we mean.” They… said, “More like Britney Spears.” They were looking at a different generation of pop stars. There’s a sophistication in Grace Jones: she doesn’t conform to the idea of what a pop star is. She’s a hybrid, really, and she’s, ultimately, more like a performance  artist. She, herself, would say, “I’m from the underground.” She’s more like a cult artist, in a way, but she’s become – in the time that I’ve been working with her – more iconic, because she came back with Hurricane, and she toured, and people saw her live – and live performance is a huge part of what makes people connect to audiences – and she’s a fantastic performer; so, suddenly, all these much younger people were really excited by her performance, and they got to discover her. Although, of course, we live in an increasingly visual age, and she’s, almost, one of the first acts to have a parallel, visual language coexisting with her music. In that sense, of course, she has hit the collective unconscious of new generations, because of the strong visual nature of what she’s done.

artist. She, herself, would say, “I’m from the underground.” She’s more like a cult artist, in a way, but she’s become – in the time that I’ve been working with her – more iconic, because she came back with Hurricane, and she toured, and people saw her live – and live performance is a huge part of what makes people connect to audiences – and she’s a fantastic performer; so, suddenly, all these much younger people were really excited by her performance, and they got to discover her. Although, of course, we live in an increasingly visual age, and she’s, almost, one of the first acts to have a parallel, visual language coexisting with her music. In that sense, of course, she has hit the collective unconscious of new generations, because of the strong visual nature of what she’s done.

MD: She’s going to be headlining a big music festival here in Auckland in about two weeks, and chances are, ten years ago, like you say, that probably wouldn’t have happened, but her cache has changed considerably.

SF: Yeah…. It is really interesting. Even Chris Blackwell said – about a year ago, when I was in Jamaica seeing Grace and showing her the rough cut – “Grace is bigger now than she’s ever been!”

MD: Yep! And I can’t wait to see her… perform. It’s going to be amazing, I’m sure.

SF: She loves that relationship with the audience. She really loves the higher stakes, and she brings an intimacy to that moment as well.

MD: You knew her, for a while, before you started making the film. Did you learn much about her as you were making the film? Was your perception, of who she was, different at the end of the film making process, than before it started?

SF: There’s always a fear, when you’re making a film, that things are going to fall apart, because it’s not an actor playing a role; it’s a person’s life. That’s always the anxiety for a documentary maker. I feel like Grace has always been rock steady… from the first moment that I had that long conversation with her, after she’d seen the film I made about her brother. We just hit it off, and it was a, sort of, conspiratorial feeling; and that hasn’t, ever, changed. I’ve seen the world change around us, and, of course, I’ve got to know her better, and… there are moments, that you see in the film, when she tells that story about her enacting step-grandfather onstage. That was just riveting. I’d never heard that before, in those moments. I feel like all of the range of who she is: it always amazes me how warm she is, and she’s extremely funny as well. I think she’s a liberating person.

SF: There’s always a fear, when you’re making a film, that things are going to fall apart, because it’s not an actor playing a role; it’s a person’s life. That’s always the anxiety for a documentary maker. I feel like Grace has always been rock steady… from the first moment that I had that long conversation with her, after she’d seen the film I made about her brother. We just hit it off, and it was a, sort of, conspiratorial feeling; and that hasn’t, ever, changed. I’ve seen the world change around us, and, of course, I’ve got to know her better, and… there are moments, that you see in the film, when she tells that story about her enacting step-grandfather onstage. That was just riveting. I’d never heard that before, in those moments. I feel like all of the range of who she is: it always amazes me how warm she is, and she’s extremely funny as well. I think she’s a liberating person.

MD: You mentioned the style of films, or the way you approached making this documentary. Were there documentary makers – film makers – that you were inspired by, that, maybe, you checked out growing up, or have seen along the way?

SF: Observational is possibly too passive a term, but I’ve always loved the observational approach. The great masters of that being the Maysles, the Frederick Wisemans, Pennebaker, and I also like the Russian school of poetic documentary, like Kossakovsky. There’s a different kind of tone to the film… and I’ve always been a huge admirer of Herzog’s documentaries, particularly his earlier ones; the more strange ones, where he’s talking less. I’ve always like that sort of sense of the smell of his films; it’s always fascinated me; so, I’m much more interested in capture than I am in commentary. I’m interested in the creating of a document, and that’s the kind of small attempt to mitigate mortality; and there’s something beautiful about that as time, with change, moving on, and you create this small pause. It’s a document. I come from a background of painting, and I think that a lot of painting is like documentary: it’s creating…this a portrait, really, not a linear biopic; that you’re tracking a time line. It’s more like boring through the layers of her being, and discovering the different…. In a sense, it’s a bit like an orchestral piece: there are different movements.

MD: Do you have another film in the pipeline? Have you got something else in the works?

SF: I really want to complete my trilogy with Slavoj (Zizek), and it’s just a wonderful excuse to nosedive into filmmaking, and thinking about film and what film does. The cinema is my absolute love, even though I make documentaries. I’m interested in the relationship between fiction and cinema, and documentary and cinema, and how you can use a cinematic language within a documentary context. That’s why I’m always delighted that people will see this film in the cinema, because it’s mixed to work in that space – it was made to work in that space – selectively as well.