Interview: Blue Note’s Gregory Porter Talks to The 13th Floor

The folks at Blue Note Records have been putting one fine jazz release out after another this year. The latest is by vocalist Gregory Porter.

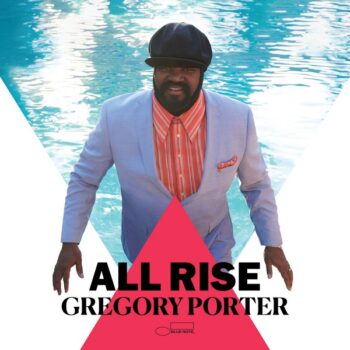

The Grammy-Award winning artist has just released All Rise, his 6th album.

One of 7 siblings, Gregory’s world was rocked earlier this years when his brother Lloyd succumbed to the COVID virus.

With his new album getting rave reviews, Gregory Porter talks to The 13th Floor’s Marty Duda about All Rise.

Listen to the interview here:

M: How are things in California? We hear all the stuff about the fires and COVID and everything.

G: It’s as bad as you say, as bad as you think it is.

M: Really?

G: The smoke is kind of crazy in different parts of the state. You know, the air was clearer here than it was in the Central Valley where I live, so we decided to come here for just a few days to get up on the mountaintop and breathe some fresh air.

M: Makes sense. I mean, it’s got to be a strange time. How are you feeling about the fact that All Rise has just come out a few weeks ago and this is all going on in the meantime?

G: It’s a duality of my feelings. I don’t like the fact that I’m not able to perform the music and support it like it deserves, but I like the fact that this is the type of record that I made at a time like this. Even though I wrote the songs before we went into lockdown and before we had protests and before there was a problem with political truth, there are some messages on the record that speak to the time that we’re in. I’m glad I made it a timely record for where we are. It’s optimistic, but there’s also some messages of substance and inequality there as well. But yeah, it’s unfortunate that I’m not able to work it like I would like.

G: It’s a duality of my feelings. I don’t like the fact that I’m not able to perform the music and support it like it deserves, but I like the fact that this is the type of record that I made at a time like this. Even though I wrote the songs before we went into lockdown and before we had protests and before there was a problem with political truth, there are some messages on the record that speak to the time that we’re in. I’m glad I made it a timely record for where we are. It’s optimistic, but there’s also some messages of substance and inequality there as well. But yeah, it’s unfortunate that I’m not able to work it like I would like.

M: I’m sure it’s got to be frustrating. Since you had some of these songs that have messages that are relevant to what’s going on, is this stuff that you’d been thinking about for quite a while?

G: Well, the equality story is as old as humanity. I think in a way, a song like Mister Holland is speaking to all those questions of equality, being treated like a regular Joe or average Bill. This is the question that the people are asking for. Whatever the regular thing is, give me that. I don’t want superior treatment, I don’t think I’m above anybody, I just want the regular treatment. Which, in the case of police brutality, is just not getting shot. It’s not having to be subjected to this type of thing, this type of danger. Even if no physical damage happens, the threat of it is continually there, and I’ve faced some of it in my life. So yes, it is something that I’m speaking of, even though the message is cased in a sweet puppy love kind of story. I’m thanking Mister Holland for treating me regular. Thank you for not making any trouble of my skin. It’s not a problem, nor has it ever been. Not for my mother, not for my grandfather, not for his grandfather before that. All of that was wrong. This is my kind of approach, always to say my protest is generally subtle in that way. Sometimes it can seep into the head a little bit more if it’s subtle.

M: Definitely. I did a radio documentary speaking to a lot of the old musicians from the 40s and 50s. A lot of these were blues musicians, black musicians who would tour the South, and the stories they told me about the incidents that have happened are just appalling. You like to think that was 50, 60, 70 years ago and that these things don’t happen now but it’s clear that that’s not necessarily the case.

G: No it’s not, and this is the thing about cellphones and documentation. There’s been large and small disrespects that have never been caught on camera. This happens so many times that to have it documented now… the blowback that you see is not just because of one incident. It’s for the time your cousin got shot and no cameras were there, no great lawyer came to talk about it. It was just dismissed. I don’t know if nobody will bring up those stories, nobody will ever talk about those people. It’s just gone away. It’s that time when you know your uncle got locked up for an unjust cause. There’s a backlog of things that people don’t know about. So when they see people protesting, ‘oh they’re protesting over this person, why do they care about him?’ Well, it’s not just him. It’s systemic. When people talk about systemic, it’s something that has been going on a long time. Listen, we could talk for hours about that.

M: I hear you! We do wanna talk about the record itself. I see that you recorded at Capitol Recording Tower in Hollywood, I’m curious about that because it’s such an iconic building. What was that like?

M: I hear you! We do wanna talk about the record itself. I see that you recorded at Capitol Recording Tower in Hollywood, I’m curious about that because it’s such an iconic building. What was that like?

G: Oh, amazing. We started the record there, we did about 5 songs there, and then recorded in a little spot in Champ de Mars in Paris, then we finished up the record in London at Abbey Road with the London Symphony Orchestra strings.

M: Nice. Was the ghost of Nat King Cole there or what?

G: Absolutely. You know, I recorded those with Nat King Cole’s microphone. They have his and Frank Sinatra’s chairs still there, and Nat King Cole’s piano is still in Studio A. It’s got some weight and some heft and some spirits in that building, so I love recording in that place.

M: Give me one of the tracks that you recorded there.

G: We did Everything You Touch is Gold, we did Concorde… it was a whirlwind of recording so I can’t quite remember what we did where.

M: Concorde leads off the album. Just tell me a little bit about the band that you’ve got playing with you, there’s a gentleman by the name of Chip Crawford on the piano, Troy Miller.

G: Chip Crawford has been my main man from the beginning of people’s knowledge about me, he’s been with me for over a decade. Emmanuel Harold has also been there from the beginning with me. Jamal Nichols, this is my first time recording with Jamal, but Jamal’s been in my live band for 5 years. Tivon Pennicott has been my regular saxophone player, been with me for years. The addition to the group is Troy Miller, who was the main producer on the project and arranger. He arranged the string arrangements, and collaborated with me on a lot of the arrangements for the record. There’s several musicians that are friends of mine, both in the US and the UK, that are on the record. The core band, the rhythm section is my band, the band that I travel with.

M: Right. So Troy is a new addition, you brought him in for this record I assume. It sounds like you had to have quite a bit of communication going on, how did the two of you work together?

G: We worked together in Paris and in London. We communicated over the phone before we got together. We had been working together many times before with orchestra projects in the UK. I also met him on the road, he was working as a drummer for Roy Eyres. I don’t know if you got a chance to hear the Nina Simone project that Universal did, he was the arranger on that.

M: He’s got the stuff then, that’s for sure.

G: He’s extraordinary, he’s a one stop shop. He plays amazing keyboards, drumming is his main instrument. He’s an arranger, an incredible multi-instrumentalist and so it’s just fun working with him cause it’s like, ‘oh, let’s put this instrument on there’. Come up with any ideas and he finds a way to bring it to fruition, he’s a great guy.

M: Now I assume the track If Love is Overrated is one of the ones you recorded at Abbey Road with the London Symphony Orchestra, it’s got some beautiful lush strings. Tell me about that one.

G: Yeah, it’s not a tradition of what I do in terms of writing these love songs to love. I’m so, I’m still fascinated by love and I’m optimistic about love all throughout romantic love and brotherly love, love of place and people. So this is in the vein of No Love Dying or Consequence of Love, it’s a love song to love. If love is cliche, if it’s for the weak of heart… whatever bad thing you say about it, give it to me anyway because I feel it’s the best thing that I’ve ever experienced. I know it is for a lot of other people, and so I wrote this song. ‘The hands that are touching me are not the ones that are supposed to be, your lips are an illusion.’ You know, if love is foolish then damn it, give me foolish!

G: Yeah, it’s not a tradition of what I do in terms of writing these love songs to love. I’m so, I’m still fascinated by love and I’m optimistic about love all throughout romantic love and brotherly love, love of place and people. So this is in the vein of No Love Dying or Consequence of Love, it’s a love song to love. If love is cliche, if it’s for the weak of heart… whatever bad thing you say about it, give it to me anyway because I feel it’s the best thing that I’ve ever experienced. I know it is for a lot of other people, and so I wrote this song. ‘The hands that are touching me are not the ones that are supposed to be, your lips are an illusion.’ You know, if love is foolish then damn it, give me foolish!

M: Very good. And on the flip side, another track Phoenix is very funky. It’s got horns and organ and a sax solo.

G: It’s unintentional, the different genres that are used. The Gospel feel, Funk and Soul, the absolute Blues feels that are on the record. This is probably what I’ve done in my career. I’m a Jazz singer, but I use of all the devices, the cousins of the music, to express myself. Phoenix is a song that we played in a whole bunch of different type of styles. It swung towards Marvin Gaye, then it went another way, then I settled on a feel and I was like, that’s it. That’s where we want to go with this song. Phoenix, it’s got that funky vibe for sure.

M: Definitely. Obviously the focus of the album should be your vocals, and I think probably the vocal performance that I admired the most was on You Can Join My Band, which also has a beautiful piano solo in it. When you’re singing, when you’re recording these things, what’s going through your head? Are you thinking about the songs, or listening to the music. Do you have people around you that are urging you on and giving you input?

G: No, I’m both working on my vocal and directing my instrumentalists what it is that I want to hear. Because Chip my piano player has been around for so long, he’s played all different styles of music. I don’t have to sit with him for 5 hours and explain what it is that I want. I tell him, a congregational song as if you were at the very last few minutes in a church service in a black church in Louisiana. This is the altar call, this is when you call everyone up to the front of the church for the last ‘we are gathered here today.’ He knew exactly what I was talking about, and so that was exactly what we go right into. This song is essentially me again, trying to bring the downtrodden, the least one. This song in a way is like Take Me to the Alley. If you’ve ever been left on the outside, if you’re down and out, if you’ve been mistreated… I still want you, I still believe in you, I am still thinking about you. This is the underdog story, and I feel like I’m the underdog and I’ve always rooted for the underdog. I think some members of my band, Chip Crawford, in a way he’s an underdog. He thought the meat of his career was over. We both met at a small Jazz club in Harlem, and ‘no it ain’t over, I still got something, I haven’t started yet at 40 years old. Even though you’re 20 years older than me, let’s go. Pack your bags and let’s go.’

M: I like that. I was reading some reviews to prepare to talk to you, and I see the Rolling Stone magazine claims that they think you were channeling Luther Vandross, and I was wondering if he’s a guy that you think about.

G: They did say that, in particular for one of the songs, Everything You Touch is Gold. In a way, this ‘if only for one night’, the way Luther used to extend songs and turn it into a long love making version. I did that with Everything You Touch is Gold for sure. It’s one of those R&B songs that are in the tradition of the music. The lyric, there’s a bit of hyperbole there, a bit of over-the-topness there, but that’s the way love is. This is what the man or the woman is saying. It’s like: ‘you have knocked me off my feet.’ You go, has she really knocked you off your feet? But it makes you feel like that. I feel like I’m walking on clouds, you name the R&B or the Soul song, and that’s the type of thing that I was trying to get. It’s archetypal in a way. This is like the archetypal Blues songs, Gospel renderings, Jazz songs, quintessential. In a way, I probably trying to say everything that is my music is on this record. Not everything, but the meat and gist of who I am and what I’ve been influenced by is on this record.

M: You mentioned the different genres; there’s Blues, there’s Jazz, there’s R&B. But the last couple of tracks, Thank You and Revival are both pretty solid Gospel tunes. Did you want to leave on that note on purpose?

G: Yeah, without question. I even mention it in Thank You. Right between Lakeview and Hayley Street, that’s where the outdoor church would meet. When I was 9 or 10 years old, that was the place where I really found my voice and found that music was this really powerful thing in my life. Without question, that’s what I’m saying there. The sounds of those songs are quite frankly the sound that you would have heard when I was a little boy in church.

M: Is that back in Bakersfield?

G: Yes, in Bakersfield, California.

M: It’s interesting because a lot of people think of Bakersfield as the country and Buck Owens and all that. Were you aware of that when you were growing up there?

G: Absolutely, country music has influenced me whether I like it or not. And I do like it. George Jones is my man, and Merle Haggard has lyrics upon lyrics. I would say that Bakersfield is populated with that migration that came from the South, and so the black migration that came from Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas; those people brought that southern gospel sound to central California. That’s what I drew on as a young man, and that’s what feeds my music. That’s what people hear. The emotional sensitivity and renderings that you hear, that was learned in the church pews of Bakersfield, in a little small church with no air conditioning.

M: What have you got planned for us next? Are you thinking about the next project?

G: Yeah, I am. I’m uncertain as to what it would be, because this time that we’re in is producing such strong emotions: from the loss of my brother to the extreme difficulty yet beautiful things that I see every day. I’m uncertain as to which way [it’ll go]. It’ll probably still be optimistic, but there will be definitely be some messages about this time and what we’ve lost, what I’ve lost personally.

M: Yes, I’m very sorry to hear about your brother, that was very sad.

G: Thank you. But I’m optimistic, yet even concerned about what the next thing is going to be because I’m going to have to go there emotionally. If I am a person who writes from personal experience then I’ll have to go there, so we will see. The funny thing about this record in some kind of prophetic way; the very first song I started writing was a song about death. It didn’t make it on the record, but the name of the song was Remember Me When I’m Gone. In some way I feel like I didn’t know that I was writing a song for my brother, and I was. I put it away. I was like no, that’s not the kind of message I want to put. I had no idea that it would be as timely as it was.

M: Well, thank you very much for taking the time to talk to me. I really appreciate it and enjoyed the record immensely. I’m glad to see that you’re doing fine. Hopefully it’ll do everything that you want it to do, and hopefully you’ll be able to perform in front of a live audience again soon and do all the stuff musicians should do.

G: Thank you so much, man. You stay safe, I appreciate your wishes.