Ludovico Einaudi – The Summer Portraits – Kiri Te Kanawa Theatre: January 31, 2026 (13th Floor Concert Review)

Even before a single note was played at Kiri Te Kanawa Theatre there was kind of anticipatory hush . The kind of collective stillness that signals not excitement so much as readiness.

Lodovico Einaudi’s audience understand what is to follow. His music doesn’t announce itself rather it persuades through the patient organisation of time—iterative cells, incremental registrable growth, and harmonic rhythm calibrated to the body’s sense of breath.

Einaudi’s position in contemporary musical culture remains distinctive. Trained in the European conservatory tradition yet formed in the wake of late‑modernist and post‑serial aesthetics, he has moved toward a post-minimalist idiom whose surface simplicity can obscure the sophistication of its pacing and voicing. In performance, the interest often lies less in ‘what happens’ than in how a limited set of materials is re‑weighted—through pedaling, balance, and timbral blend—until a familiar figure is experienced as newly inflected.

The current tour centers on The Summer Portraits, released in early 2025 and conceived as a cycle of musical ‘paintings’ prompted by a set of rediscovered canvases in a Mediterranean villa and capturing the memories of the summers of youth. In Auckland the new material did not feel appended to the back catalogue but integrated into it, as if the album’s quieter, more textural writing had retroactively reframed earlier pieces.

Born in Turin in 1955 and trained at Milan’s Conservatorio Verdi, Einaudi’s early encounter with Luciano Berio provides a useful historical anchor: not because his mature style resembles Berio’s, but because it clarifies what Einaudi has refused. Where the avant‑garde often pursued discontinuity, Einaudi has doubled down on continuity on the expressive potential of sustained pulse, consonant sonorities, and gradual change. That commitment demands discipline without structural pressure, the music lives or dies by proportionality, control of harmonic pacing, and the capacity to shape long‑range crescendi without resorting to rhetoric.

The production matched the aesthetic: near‑darkness, a single warm pool of light at the piano, and softly abstract projections. The effect was not decorative but functional, emphasising the concert’s attention to micro‑change. Importantly, amplification and electronics were used as extension rather than effect: to stabilise the piano within the ensemble texture, to widen the perceived dynamic range at low volumes, and to add a faint halo to string sustain.

Einaudi does not present an evening as a sequence of discrete numbers. The programme moved as a through‑composed arc in which recent works circulated alongside established pieces, linked by shared techniques: ostinato figuration in the middle register, harmonic progressions that pivot by common tones, and ensemble writing built on stratified layers. The result was a continuity of state—less ‘setlist’ than a single extended meditation with local shifts in temperature and density.

Obviously central to the evening were the newer works. Amongst the highpoints from the album were.

Rose Bay reflected the evening’s tone with a calm, almost metronomic steadiness. The piano part sat in a comfortable tessitura and relied on small‑interval motion; interest came from the management of resonance—half‑pedal to retain warmth while preserving harmonic clarity—and from the ensemble’s flickering, high‑register colour that read as timbral punctuation rather than melodic commentary

In To Be Sun, expansion was achieved through harmonic widening and registral bloom. Einaudi allowed the pattern to ‘open’ by increasing the spacing between voices, a technique that creates brightness even at moderate dynamics. The ensemble’s entry points were carefully timed to thicken the spectrum without masking the piano; the music’s implied brightness emerged as a function of voicing and spacing.

Punta Bianca functioned as a central statement, exemplary of Einaudi’s layered accretion. A repeating piano cell served as structural ground while inner voices shifted by step and common‑tone substitution, subtly re-colouring the harmony. The most compelling aspect live was balance: strings were mixed to support the piano’s transient rather than compete with it, and dynamic shaping was governed by long‑range contour rather than bar‑to‑bar emphasis. The performers’ task is the maintenance of forward motion through timbral and registral change.

Santiago broadened the palette via more flexible articulation and a sense of breathing rubato within a stable pulse. Rather than strict mechanical repetition, the figuration was inflected—slightly varied accent placement, minute agogic delays at phrase turns—creating the impression of travel without urgency. The ensemble’s role here was to provide depth of field: cello sustain and electronic haze enlarging the harmonic background while the piano provided the narrative.

A striking point of concentration arrived with Maria Callas. Reduced to essentials, thin textures, exposed intervals, and deliberate harmonic rhythm. Einaudi’s touch was notably controlled: attack softened, release clean, allowing silence to function as a structural element. In a hall of this size, the piece’s success depends on collective listening; the audience supplied it, and the music’s vulnerability registered with unusual force.

Pathos provided the programme’s principal intensification. The familiar Einaudi strategy of iterative patterning with incremental thickening all handled with an almost classical sense of proportion: the crescendo felt architected rather than emoted. Importantly, the released remained proportional. Even at its fullest sonority the texture remained transparent, and the return to stillness functioned as a formal cadence, restoring the music’s baseline of restraint.

Interleaved with the newer pieces were works from the back catalogue. The danger in such repertoire is automatism; the achievement here was interpretive responsibility, treating familiarity as a reason for precision, not indulgence.

In Nuvole Bianche, the emphasis fell on cantabile voicing. Einaudi resisted over‑rubato and kept the melodic line supported but not over‑projected, allowing the inner harmonies to supply colour. Pedal technique was again central: sufficient sustain to maintain legato, but with clean harmonic changes so the piece retained clarity rather than melting into wash.

Fly introduced a more insistent rhythmic profile. Yet the propulsion was moderated, achieved through consistent articulation rather than percussive attack. The patterning suggested motion without urgency—minimalist technique used for kinetic drift rather than drive.

I Giorni arrived with the weight of recognisability, and Einaudi’s choice to keep it largely uninflected proved musically sound. Its simplicity can feel fragile if sentimentalised; here it was allowed to be plain.

Una Mattina restored a reflective plane, its familiar contours shaped with lucid phrasing and unhurried tempo—less a showpiece than a reminder of how much Einaudi’s language depends on patience.

Divenire remained one of the evening’s major structural peaks. Its expansion to a broad, almost architectural swell was achieved through registral enlargement and dynamic layering rather than mere loudness; the sensation was of a space opening rather than a volume increasing. Swordfish, by contrast, briefly introduced angular rhythmic edges—tension by contour—before the programme returned to its prevailing equilibrium.

The finale, Experience unfolded as a study in cumulative energy. Instantly recognizable. Its large‑scale repetition was less about hypnotic stasis than about controlled harmonic trajectory: a gradual brightening achieved through incremental chordal re‑voicing and textural thickening. The ensemble’s coordination mattered most at the crest, where bow speed, articulation, and electronic reinforcement had to align to keep the massed sound focused.

The Tower was a perfect powerful a concise demonstration of Einaudi’s late style architecture, built from a tightly constrained piano cell whose additive extensions create subtle metric ambiguity and a sense of vertical ascent; the ensemble’s gradual layering—upper string suspensions functioning as harmonic “floors,” bass and cello establishing a quasi pedal foundation, and electronics supplying micro rhythmic shimmer—formed a timbral stratification that rose in registral space, culminating in a point of textural saturation after which the layers withdrew in reverse order, leaving the opening motif exposed and contextually redefined, a closing gesture that withheld sentimentality in favour of structural clarity and proportion

Einaudi’s playing is defined by economy. Gesture is pared back; expressivity is located in touch, voicing, and timing. The slightest delay before a harmonic change, or a marginal emphasis on an inner note, can reorient the listener’s sense of direction.

Around him the seven member ensemble includes long‑time collaborators Federico Mecozzi (violin/viola), Redi Hasa (cello), and Francesco Arcuri (electronics/percussion) together with Alberto Fabris (electric bass / musical direction). Gianluca Mancini (keyboards) functioned less as an accompaniment group than as an extension of the piano’s resonance. Mecozzi supplied brightness and lift in the upper spectrum; Hasa anchored the texture with warm, vocal sustain; Arcuri’s percussive detail expanded the timbral field without obscuring the acoustic core. The ensemble’s most impressive attribute was its control of blend. Dynamics were shaped to preserve transparency, and the group’s internal balance suggested chamber‑music listening rather than amplified crossover.

The Auckland performance confirmed that Einaudi’s aesthetic is not a retreat from complexity but a reallocation of it: away from thematic development and toward time‑design, resonance, and proportion. The concert asked the listener to value micro‑events—minute shifts in voicing, the slow recalibration of harmonic colour, the controlled dilation of texture. In that sense, The Summer Portraits reads not as nostalgic reverie but as a mature refinement of an idiom that has always prioritised continuity over disruption.

What is left with you is not just the melody so much as an imprint memory of the pacing and how the room learned to listen to small changes. The achievement is quiet, technical, and deeply persuasive.

The Summer Portraits may be rooted in personal memory of Einaudi’s childhood, but in performance, our memories become collective. Tonight felt like losing oneself in the summers of childhood —a warm evening, a long coastline, a still moment before the world grows loud. It was an evening of saudade, built gently and dismantled tenderly. A rare night of beauty from an artist who can hold a room in the palm of his hand and let it breathe.

There were three standing ovations.

John Hastings

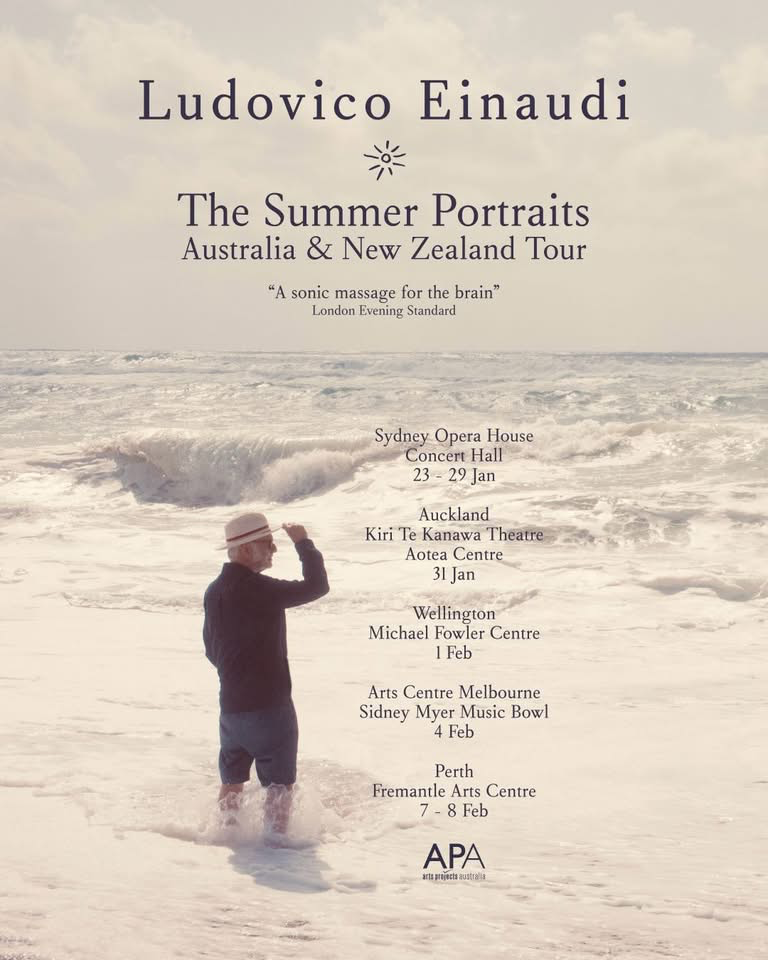

The Summer Portraits tour continues…see below:

- Violet Hirst — Auckland Old Folks Association: February 1, 2026 (13th Floor Concert Review) - 02/02/2026

- Ludovico Einaudi – The Summer Portraits – Kiri Te Kanawa Theatre: January 31, 2026 (13th Floor Concert Review) - 01/02/2026

- Wheatus – The Tuning Fork : January 27, 2026 (13th Floor Concert Review) - 28/01/2026