The Bikeriders Dir: Jeff Nichols: A Star-Studded Misfire (13th Floor Film Review)

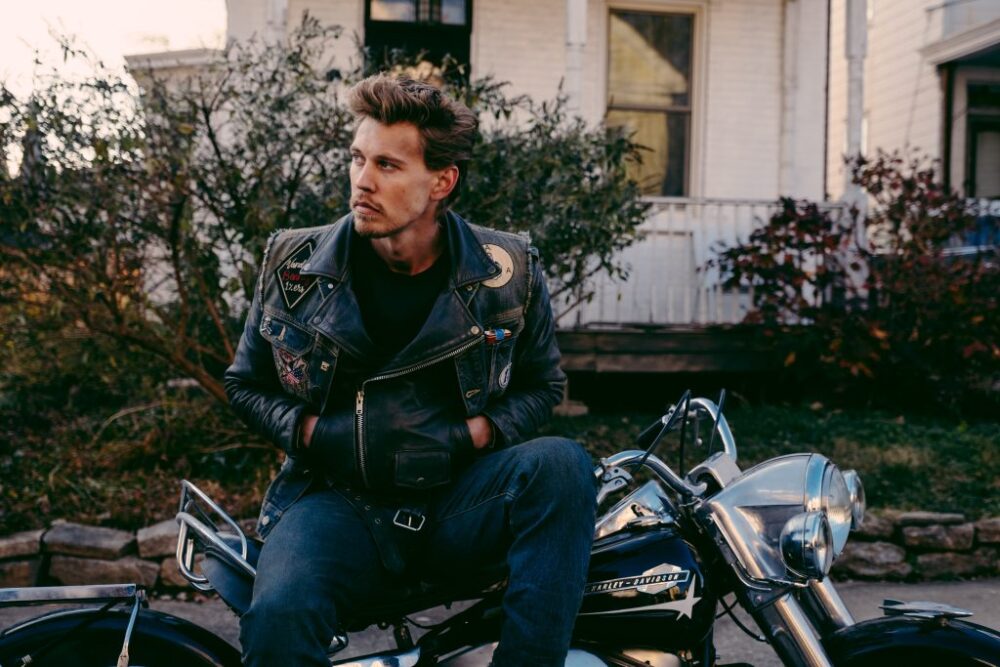

The Bikeriders has all the makings of a great film, but it’s a sanitized and generic crime drama that doesn’t say much. But it is sumptuous to look at, with picturesque shots of rumbling motorcycles, hazy dive bars, chiaroscuro lit chatter, and Butler doing his best blue steel.

Austin Butler, Tom Hardy, Michael Shannon, Damon Herriman, Jodie Comer, and your Challengers crush Mike Faist makeup part of an all-star ensemble cast. Add in the celebrated director Jeff Nichols, with his first feature in seven years and an absorbing source text that depicts an outlaw motorcycle club in 1960s Chicago.

Austin Butler, Tom Hardy, Michael Shannon, Damon Herriman, Jodie Comer, and your Challengers crush Mike Faist makeup part of an all-star ensemble cast. Add in the celebrated director Jeff Nichols, with his first feature in seven years and an absorbing source text that depicts an outlaw motorcycle club in 1960s Chicago.

Director Nichols first came across Danny Lyon‘s photography book over twenty years ago. Lyon, a photography student from 1963 to 1967, travelled with, lived the lifestyle and photographed the Chicago chapter of the Outlaws Motorcycle Club, attempting “to record and glorify the life of the American bike rider.” Nichols was struck by how ‘cool’ this book and its subjects were. Now, having adapted it into The Bike Riders, Comer as Kathy, Hardy as Johnny and Butler as Benny take centre stage. You can’t forget Butler’s character name. It’s tattooed on his arm—a glance down from his ruggedly handsome face that always has a smouldering cigarette perched between his lips. Together, the trio make an electric first 45 minutes. The film is a love triangle of sorts, framed by Faist as Lyon and his interviews over several years with Butler’s wife, Kathy, played by Comer, who is a commanding presence.

The Wild One, the ‘original’ outlaw biker film, is a seminal text for Johnny, who founded the Vandals. Marlon Brando‘s character, whose name is also Johhny, became an influential symbol with his Triumph Thunderbird 6T, black motorcycle jacket and tilted cap. The Vandals, often referred to as “The Club”, is a haven for ‘undesirables’ seeking to be a part of something as the counter-culture movement of the 60s roared in focus, shattering social conventions. As The Bike Riders expands in scope, we’re introduced to a sprawling number of dispensible and forgettable characters, bar Michael Shannon as Zipco, who has a scene-stealing monologue. The film wanders off-trail, sidelining Comer’s, Hardy’s and Butler’s love triangle.

One scene early in the film between Hardy and Butler is astonishingly intimate. But this is as good as The Bike Riders gets, and for the latter two-thirds of the film, it is running on fumes, coughing out hollow commentary on masculinity, homosociality and freedom. Like the men in the Vandals, who performatively smear grease and dirt on their clothes, The Bike Riders is a faux evocation. Unlike the photography book the film is based on, The Bike Riders is more aesthetic than authentic. Nichols is enamoured with the mythos of these men and doesn’t dare to delve deep enough to shatter the illusion they conjure. He’s not concerned with the film feeling ‘lived-in’, but rather how cool Butler or Hardy look riding their motorcycles into the sunset.

Thomas Giblin

The Bikeriders is in cinemas now.