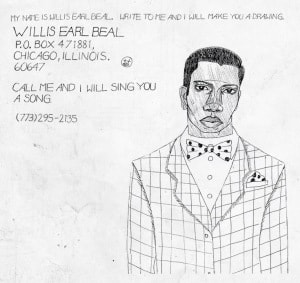

Willis Earl Beal: Talking To Nobody (Interview)

Willis Earl Beal has made one of the most stunning albums of the year with Nobody Knows (check out the 13th Floor review here). The 13th Floor had the opportunity to speak to Willis Earl Beal and discover that the man himself seems to be just as extraordinary (and outspoken) as his music.

Click here to listen to the interview with Willis Earl Beal:

Or read a transcription of the interview here:

MD: Well, I’ve had a chance to listen to your album, it’s a very impressive piece of work, but even before I got a chance to listen to it, the first thing I noticed about it was the little writing along the side of it, “I am nothing; nothing is everything” which kind of—

WEB: Hey, did you dig the manifesto? There’s a manifesto inside there.

MD: Yes, I was gonna get to that as well! So perhaps you could… cause that kind of thing puts you in the mood, I guess, for the music in some way, it kind of sets your mind in a certain way – is that your plan, is that why you include something like that? In order to give the listener something to go with?

WEB: I’m not entirely sure, actually. I guess, how it relates to the music is that, see the music itself is a hyper-focus on the minutia of this sort of human existence. My thoughts may generalise thoughts of this solitary protagonist of nobody, which is everybody. So the music itself focuses on the feelings. The manifesto focuses on what creates the feelings, and what is a good way to free one’s self from those feelings. I had already written a lot of the songs in Albuquerque, and the ones I didn’t write in Albuquerque I wrote them independent of that thought, but what occurred to me was that I wanted to be more than just another self-centered egomaniacal artist who put out these little stupid songs about his stupid feelings and it doesn’t mean anything! I needed to create a package, not just a CD, that could transcend music and art, and this push for progress, and this push for quote unquote “excellence”. I wanted to create something that was expansive in that way, something that was even bigger than my stupid name. So that was the reason for the manifesto.

MD: That’s a pretty ambitious way to approach , putting together something like that. Why is that important to you, to make a major statement, rather than just putting out your songs?

WEB: Because all of these artists, all of these musicians, all of these businesspeople and people who make money, they all think that what they do is so important. None of these things are important. You already know that the earth is just like a speck in the eye of infinity and we all walk around and we divide ourselves into this hierarchy and we tell each other, “Oh you’re less than and you’re more than, oh, the musician on the stage, he’s higher because you see he’s special, and the people in the audience are the spectators”. And I guess I’m tired of standing on a stage, not that I’ve been standing on a physical stage for a long time, but the stage of my role, and I’m also tired of looking at people on stages and being told that these people are better than me in some way. So I guess it started out from a very small point of feeling like I wasn’t a part of anything, and it just augmented itself into something very broad, very general. So there’s a lot of small-mindedness that’s motivating it, but I’d like to think that maybe it’ll have a larger effect than just my resentment and my small-mindedness.

MD: But there would people that would say you need a certain amount of ego to be able to present your music to other people and to get up on the stage and perform it. Otherwise you wouldn’t be able to do that, if you didn’t have that strength of your own convictions.

WEB: Well, performing the music on-stage was never something that I really wanted to do at all. When I was creating, whatever you call that, in Albuquerque, I was thinking of myself as some kind of novelty, some sort of myth, some person that doesn’t really exist, something that you happen upon and you pick it up and you listen to it and it’s not the best thing you’ve ever heard but it’s got some kind of mystique about it because it’s a physical thing, there’s a face on there, and you wonder about the story behind it and then you put it a part of your collection. But the person behind it – it doesn’t matter who the person is. So for me, even now, I just wanted to write songs and be respected for those songs and respected for my aesthetic. As far as having to go out there and actually represent my aesthetic, that’s a whole other beast. That’s a whole other kind of prostitution that I don’t feel comfortable with.

MD: Right. So do you feel that you got the respect that you were looking for, when the first album was released?

MD: Right. So do you feel that you got the respect that you were looking for, when the first album was released?

WEB: Absolutely not, because I made that record in a completely self-centered way. First of all I was just starting out, so it’s extremely primitive, and people were judging that as though I had crafted it for them, when in fact it only consisted of 11 or 12 songs, out of 150 songs that I had written, and they were the most primitive out of all of them. And none of them were done with other people in mind, they were done as a sort of a “DIY” – that’s the bullet point word these days, but I just did them from heart and with feeling. And critics were judging it as though it was supposed to compete in a commercial arena. To criticise art and music in general is completely archaic, but to criticise that is like criticising a child’s drawing. And it really frustrated me, because I had put myself through that process of learning how to overdub, and learning how to layer but with really, really primitive equipment. By the time I got to a studio I was ready to go, I was ready to create something big and something that sounded good.

MD: I guess what you did probably was set up a certain expectation for some people, with the first album, that this is what you wanted to sound like, this is your aesthetic. And then suddenly with the new album, it’s not exactly what people wanted from you, and so they’re going to, in some instances, probably kick against that.

WEB: You know, I think for the most part the reception for the new record has been pretty positive. But I also felt this kind of pressure, where there was a lot of hype that was surrounding me before. Because everybody thought it was going to be like these Alan Lomax field recordings, this modern day blues shit – they were calling me the next Robert Johnson and all this bull. And when it came out it was just this ragged disparate collection of… we don’t even know what it is. It’s just racism and it’s categorisation and it’s the industry and it’s the media and – you know, I’m bitching, but you understand what I’m saying.

MD: I do indeed. I guess it’s part of the commercial process, they have to find a way to tell some kind of story behind you, and stick with that story because that’s what gets people’s attention, even when it should be just the music that should do the talking.

WEB: And that music could not talk for anybody. I’m not criticising the music, I’m just saying that for me personally it’s not good music. It’s not the kind of music I wanted to show to the world. It was something that I could look back on and say, oh this is a part of my history, this is part of my archives. But, you know, when it comes to making a presentation to the world, you want to show your best. You don’t want to come off as an idiot.

MD: So do you feel you’ve been able to do that with the new album?

WEB: I’m very proud of Nobody Knows. It’s everything that I’d always heard, or at least everything that I’ve heard in the short amount of time that I’ve been focused on making music. And I’m very proud of it. But I’ve already even recorded a record that’s completely different from that.

WEB: I’m very proud of Nobody Knows. It’s everything that I’d always heard, or at least everything that I’ve heard in the short amount of time that I’ve been focused on making music. And I’m very proud of it. But I’ve already even recorded a record that’s completely different from that.

MD: Already in the can?

WEB: Yeah.

MD: [laughs] That’s amazing! And is there a plan to release that relatively soon, or do you have to give this one a chance to do its thing first?

WEB: If I could I would release it tomorrow, but I’ve gotta let this one do its thing.

MD: I agree with you, I think this new album is a very impressive piece of work. The first two tracks really grabbed me and sucked me into the whole thing. The opening track, Wavering Lines, just a beautiful piece of work. I wanted to ask you what wavering lines represent to you. Does it coincide with the art that goes along with the record?

WEB: Yes, but you see, everything coincides with itself in the package. It’s all haphazard. I can’t say that it all started out as an intentional thing, that everything matched up and everything linked. But I think that it’s got a lot to do with the way I look at life, the interconnectedness. It’s got a lot to do with my spiritual beliefs and how I’m pretty much thinking the same way all the time. My psychology goes into the way I draw, goes into the way I write, goes into the way I create music, and the disorganised way I live my life. But things always seem to just wrap themselves up. Every time I try to fuck my life up, my life just mends itself before I can really do it.

MD: I was going to point out that a track like What’s The Deal sounded to me like it might have been somewhat extemporaneous, like you were might have been making it up in the studio as you went along. Is that how some of the creative process goes or is it more planned out than that?

WEB: What’s The Deal was made up in the studio on day one, on day one in the studio – the first studio I’d ever been in – I made that up. But I had drunk half a bottle of Jack Daniels and I was totally frightened of my manager, or who would become my manager, and I didn’t know what anybody’s motivation was, and I had already recorded like 14, 15 songs. I guess I just started to feel like I was some type of porcelain monkey who never had any control over his life, and I recorded that. But outside of that, a lot of the process does not go that way. Like a lot of the songs I wrote in Albuquerque. I had melodies already figured out for those songs, and then when I got to the studio, because I’m not trained in playing instruments, the melodies always just change in very interesting ways. I do a very rudimentary lay down – I’ll go over and hit the drums the best I can, and I’ll go over and play a keyboard or a piano or melodica or glockenspiel or whatever happens to be available at that time – stand-up bass, bass guitar, whatever, children’s toys – and if it sounds good the way it is in the mix, I leave it, and if it needs a little something, I call upon more competent musicians to execute that. So that was the process for Nobody Knows.

Click here to listen to What’s The Deal? from Nobody Knows:

MD: Gotcha. I also noticed that it was recorded all over the world – Amsterdam, Chicago, Miami, London, New York, even Utica, New York! How did it come to be that it was recorded in so many different places?

WEB: I didn’t have time to go somewhere for two months and record a whole record. I had a shitload of songs in my mind, I’d memorised them all, and we had to record the album on the fly, because we didn’t really have time to sit down.

MD: You mentioned needing to locate your motivation – along with that, I’ve heard that you’re acting in a film called Memphis, directed by Tim Sutton. Do you look at acting as just an extension of what you’re doing with your music and your poetry?

WEB: Absolutely – in fact, before I got interested in music… I had always drawn pictures and I’d always written poetry, but then I became interested in acting when I was in Chicago, because I wrote a couple of plays in high-school and I was in the Drama Club. Then I tried to become a paid actor in Chicago and I found it to be a very cold scene, so I got pretty discouraged and then just joined the army. It’s really a perfect circle, like how I was just talking about, how everything just works itself out. It’s a perfect circle, that music that I’d never entertained in my entire life ended up coming about out of nowhere and creating an opportunity for me to be in not only any film, but a perfect film that represents everything that I want to say.

MD: How much of you is in the character – I believe your character is Ezra Jack, is that right?

WEB: No, actually my character’s name changed. It started out as Ezra Jack, and then he decided to just call my character my name.

MD: Okay, so you’re almost playing yourself!

WEB: Yeah, I’m playing myself in an alternate reality. This guy, he’s very reluctant to continue being in the music industry, but he doesn’t even make a definite decision to not be in the music industry, it’s just that he doesn’t feel compelled to succeed in a conventional way. There are some figurative or literal voices in his head, and these voices are sort of pulling him, and he’s trying to figure something out, but the people around him don’t know exactly what that is. They don’t know if it’s new songwriting, or if he’s really worried or he’s on drugs. I guess I feel the same way – I feel exactly like the character. I don’t really feel compelled to win; I’m not a really competitive person. I want to feel comfortable in my own skin and live a naturalistic life, but the way society is it’s in direct contrast to that kind of person.

MD: So that must create a lot of tension between you and the people around you, working with you or for you – your label, your managers or your fellow musicians.

WEB: Absolutely, because they keep asking me, if you don’t like the industry so much, why don’t you just quit? And the reason I don’t is because I don’t know how to hunt and I don’t know how to build a house. And I lost every job I had, and I feel like the only choice I have at this point is to try to develop a voice, be a voice for free thought. Help to tell people that, okay, I’ve got this career, and I’m going to use this career to tell you that don’t be enthralled by fame, don’t be enthralled by all of the lights and the things that they jingle in front of you, because every place that you are is just another form of industry and it can be a hell. Obviously there are certain perks to travelling all around the world, but it’s not what people think it is, it’s just more obligation. You’re not always the person that you need to be in order to make money. Sometimes you feel a little weak, sometimes you don’t care about singing. Sometimes you just want to be a botanist, you just want to walk around in the forest. I don’t know, I feel very disillusioned on a regular basis.

MD: It’s a shame, because your music is so powerful and so soulful. Do you not get a sense of satisfaction from being able to make that music and have people listen to it?

WEB: Well, the reason why I don’t get that direct sort of satisfaction is because it’s all just me on tape or vinyl or CD or whatever, and also I don’t create my music from this place of skill. I don’t really see myself as a skilled individual, particularly because of the way I compose. So I don’t get that direct satisfaction of going over to a drumkit and soullessly playing a beat, or going over to the guitar and soullessly playing a couple of chords from a Buddy Guy song, I can’t do that. I have to be inspired by the particular sound of something or an instrument, and it has to create a very, very particular feeling in me. In many ways I feel like the songs come from nowhere, and then things happen, things transpire and it gets judged, and suddenly I have a three piece band and I’m on stage in front of people, and I just don’t know how it happened. [laughs]

Watch the trailer for Memphis, starring Willis Earl Beal, here.