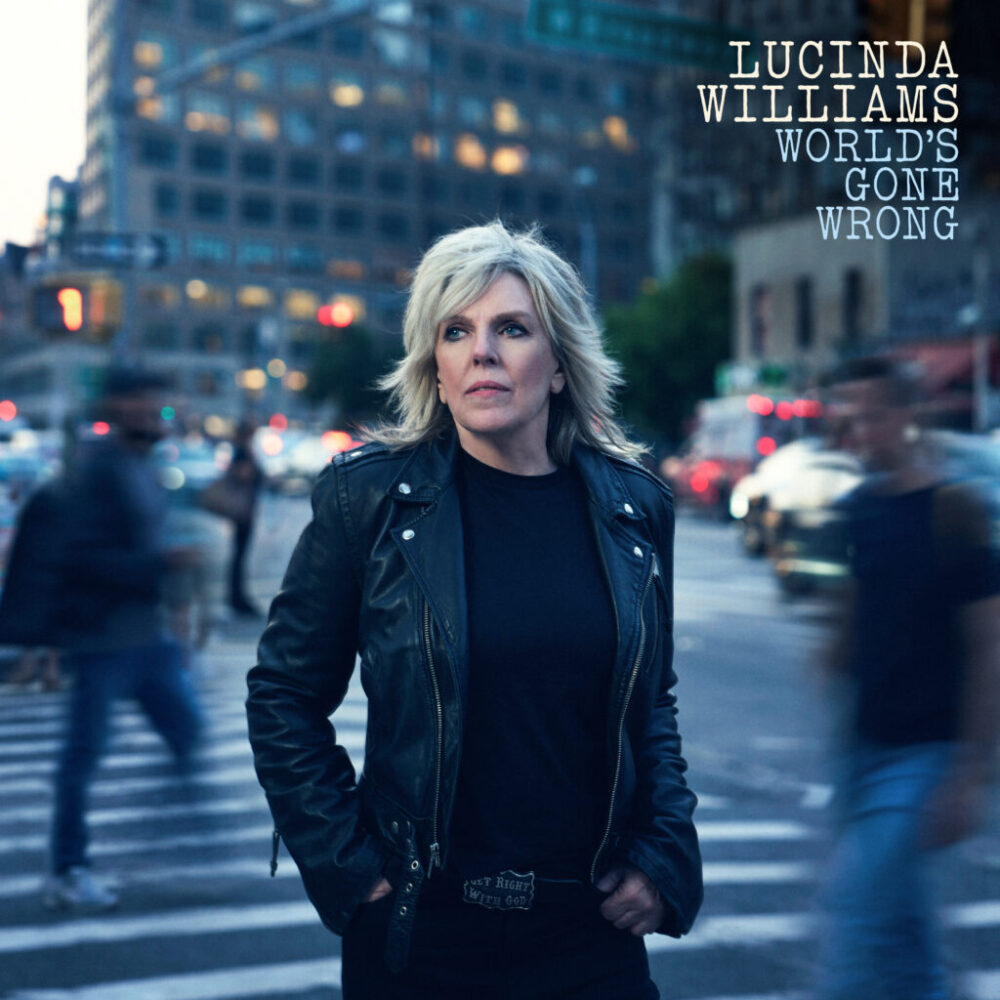

World’s Gone Wrong – Lucinda Williams (Highway 20) (13th Floor Album Review)

Just occasionally an album is released that taps into the times with laser accuracy. Lucinda Williams’ 18th studio album, World’s Gone Wrong is such a release: striking from first listen for its relevance to these angst-riven times.

Of course, angst has long been a strong thread running through Williams’ s songs. But her world-weary voice has more commonly stroked the wounds of scarred relationships and places across the American South than address universal themes. The classic Car Wheels on a Gravel Road narrated emotional landscapes and name-dropped places like Lake Charles and Jackson, Mississippi.

Here, 28 years later, Williams’ vision is less site-specific: the focus is matters of collective conscience rather than fractures of the heart. World’s Gone Wrong is less the edgy country of Car Wheels and more it’s overlap with blues, that American tradition whose tap-root lies firmly anchored in the sediments of injustice, struggle and misplaced power

Album-opener and title song pulls no punches as scene setter. An ordinary working couple grapple with twin contemporary challenges: getting by financially while also making sense of the world. Things are gettin’ tight, but it could be worse/ She tries hard to ignore the news. It’s part of a distinguished lineage of workers-doing-it-tough songs populated by Guthrie, Dylan and Springsteen. She stares out the window and shakes her head /She can’t believe the things she’s read. Anxiety and bewilderment. An anthem for these times whose sentiment continues in Something’s Gotta Give: There’s an anger/ To these days/ A simmering rage/ That never goes away). Doug Pettibone’s guitar is superb. In fact, the entire band is a collectively tight embellishment to Williams’ languid vocals.

Third song in and a change of gear. As if the heaviness of the world is all too much, the twang of Low Life suggests a need for sanctuary. Soothed by the sounds of Southern forbears (Play Slim Harpo on the jukebox/ Let me go with no shoes and socks). As well as Slim Harpo, the great Louisiana exponent of swamp blues, Dr John gets name checked too. Cocktails, jukebox, the quest for escape and connection in fragmented times….

There’s a more driving beat on How Much Did You Get For Your Soul? It’s heavily implied this song is exploring the old familiar Crossroads legend, but something larger is at work. Robert Johnson appears, but one suspects it’s may well be the soul of the nation being mourned, the dark art of the deal being a metaphor for a dream morphing into nightmare.

Mid-album, we have a cover: Bob Marley’s So Much Trouble In The World featuring the incomparable voice of Mavis Staples. A genius guest spot. Who else in her mid- 80s is still in her musical prime with a life that threads back to the civil rights struggles that defined so much of twentieth century America?

Sing Unburied Sing has all the driving guitar and drums of a Neil Young and Crazy Horse anthem, its cryptic lyric alluding to suffering and a hovering between two worlds. If the two worlds in question are the life of struggle in the here and now and the sweet hereafter then that hovering gets more direct treatment in Black Tears, the most blues- washed song of the collection. Mississippi is the state in focus and suffering the state addressed. Blood in the river, tears in the street. Four hundred years of black struggle in one song. Extraordinary.

Punchline reels back the energy level into a quieter biblically-flavoured meditation. Bob Dylan’s Slow Train Coming era comes to mind. A little more critique here, however. Over the talking-intoned guitar chords, Williams raises the theological question: His way is a mystery/ Did God forget the punchline?

Freedom Speaks could be a civil rights era Staple Singers song but it’s not; rather it’s Lucinda rallying comrades Apathy will blind you/ Until it’s way too late. There’s no letting up on the messaging here. There’s an urgency to celebrate solidarity, see the injustice and engage in the struggle. My name is freedom is the repeated fade-out.

The collection wraps up with a return to a country lilt featuring Norah Jones on piano. In fulsome Texan drawl Williams taps into a deep well of biblical imagery: We are here to bear witness/ To this monstrous sickness. These are lyrics that do more than reach up to a bible on the shelf, however. With words like We have tolerated the one we despise/ Been led astray by his disguise, the imagery is as applicable to the contemporary geopolitical landscape as old-time church values. No politicians named, just allusion. And far from a bleak ending the phrase on repeat and title of this song (We have come too far to turn around ) is ultimately a message of hope.

This is standout collection of ten songs in which the one of the great voices in that wide church called Americana is supported by an outstanding band that moves with ease from country through soul and blues. These are superbly wordsmithed songs, perhaps in some measure inspired by Lucinda’s poet-father Miller Williams. Songs that have an urgency and that apparently hastily replaced a different collection as studio time approached last year. Songs cowritten with husband, manager and co-producer Tom Overby along with guitarist Doug Pettibone. World’s Gone Wrong is an album born of the contemporary America they were written in: complex, perplexing, deeply worrying. A superb collection deeply in tune with these times.

Robin Kearns

World’s Gone Wrong is out now on Highway 20/Thirty Tigers Records