Track By Track: Roland Rorschach of The Hallelujah Picassos Takes Us Through Voices of Exhuberant HellHounds

With a career spanning more than 30 years, Hallelujah Picassos are the stuff of legend. They’ve just released a stunning new album, “Voices of Exuberant HellHounds.” Songwriter and frontman, Roland Rorschach stopped up the to 13th Floor for a track by track discussion with Marty Duda.Read or listen to the interview here.

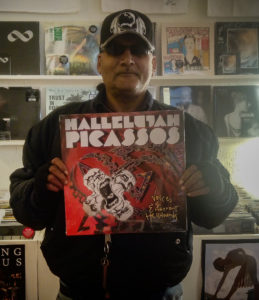

MD: So, we’re here with Roland from Hallelujah Picassos. We’re gonna talk about their new record, it’s called, “Voices of Exuberant HellHounds,” and he’s brought along some vinyl copies which we’re going to give away to some folks who are listening to this and reading this, so that’s going to be exciting. Now you started talking to be about how the record came about and working with some guys from the label.

RR: Yeah. It was at The Whammy Bar I met them. So I met Kim Martinengo, I hadn’t seen him for a long time and he mentioned that he had a label where they do vinyl only releases. And I got to thinking and I thought it might be a good idea. And then I met David Perry as well, who also runs 1:12 Records. And it was a good idea. And they wanted new material and we had new material, so one thing led to the other.

MD: So, is that a vinyl only release?

RR: Well it’s digital as well. But with vinyl, it has a bit more gravitas.

MD: Yes, definitely.

RR: It’s tactile. And there’s a resurgence in vinyl the last couple of years, so one thing led to the other and here it is.

MD: Excellent. So, how did you happen to have new material available?

RR: We started recording… the continuation of the band started in 2012 and we started writing straightaway – new songs. And apart from a couple like Black Spade Picasso Core and the bass line from Cracked Salvation it’s all new stuff – this decade.

MD: Was it hard to get the band back together?

RR: No, no the guys were keen to see where it leads them. In the beginning it was difficult because we hadn’t worked together for a long time. And then a bit of tension. But after a while it dissipated and we moved on. And I think of the writing process, I think the first one that came about was Salvadore, I had been writing and had lyrics and a melody that I sung to them and that’s the one we started on, one of the first songs – a new song that we wrote together.

MD: And of course, you lost a band member in the process. [drummer Bobbylon]

RR: Yeah. Last year. It was a big loss, you know. And when I got the phone call, the first thing I thought was he’ll never sing again because there’s very few vocal tracks that he’s done. I counted them yesterday. I think there were six. There are three or four songs he sings on with the Picassos, but they’re not on this album. This in the past. And then there are two songs he does with Ricky’s band, Trip To The Moon. And one with Terry Moana. And there’s one more with other project Sound System where he sings, so six or seven. And I think that’s not enough. Truly cos it was a dance movement, where the dance would click, and do a variation of it. Yeah.

MD: But he is playing and singing on the record.

RR: Yes, he is playing and singing. Not as much as I would have liked. Unfortunately.

MD: Right. That’s a shame. Well, let’s go through the record track by track and you can tell us… I’ve listened to it a few times and it’s a wild record! There’s all sorts of stuff going on and it’s just endlessly entertaining from beginning to end I think. So the first track is called “Cracked Salvation.” Why don’t you tell me about that one?

RR: OK So, this is a bass line from an old song on Hateman In Love called “Cracked Up.” And we started the album, Hateman In Love, back then. And so we thought we’d start this album with “Cracked Salvation.” So the bass-line is an old bass-line we used, but I wrote new lyrics for it. And I am… when I sing about gods, I don’t necessarily mean religious gods. I mean, these days we have gods in music, we have gods on Internet…

MD: This is true.

RR: You know, all that’s in the culture, so it’s in… I think it’s a criticism of that. An observation, criticism about that. How they think about it, you know what I mean? Those little things. An obvious example with the Kardashians that have a huge influence on how people dress and think. And I think that’s to the detriment of human progress, if you don’t mind me so blunt. So that’s what the song is about.

And then, Salvadore, the next one, it’s funny because Salvador means salvation in Spanish, you know. And I like certain themes to run through my songs. And Salvadore was written at a period, at a low point and I felt that there was something missing and although there are sentimental words in it, when I finished writing it and subsequently afterwards, you know, I felt not sentimental anymore. I don’t want to relive my teenage-hood.

MD: Right.

RR: The only reason why we’re doing this is because I have something more to say and it’s easier than writing a book. When you have people’s attention when you write the songs or a book, it’s a whole different quality altogether.

MD: So how do you feel about performing some of the older Hallelujah Picassos tracks.

RR: We did, actually, during the live set, we only did this version of “Black Spade Picasso Core” and we did… well we did “Hate Man” over the Red Egg and Stalag Thirteen. Where I had a variation of it. So those were the only two old songs we played. Cos, we marketed it as, we mentioned to the people that we are going to play new songs. And I’m not sentimental anymore, if we don’t play live “Next” again, it probably won’t reject the same.

MD: So this is a nostalgia trip?

RR: No it isn’t. Actually not. No, no.

MD: And how did the folks at the show react?

RR: Positive. They liked it. The album had some good reviews. The gig was very positive. It was surprising, but everyone I… we had nothing to gauge it on because we hadn’t played for a long time. So, no. It was well received.

MD: So the next track is “Hang All Bankers/Dirty Suits.”

RR: So those two songs are thematically round about the same issues. So this is a song I wrote the lyrics for Darryn’s band. He is in The Telepathics.

MD: The New Telepathics. So, this is Darryn Harkness we’re talking about?

RR: Yeah. And Dirty Suits about work for eleven in one of his songs. But we used the words again from Picassos. And Hang All Bankers is my disdain for bankers. And ‘hang all bankers’ is hyperbole! We don’t hang people anymore, you know. It’s hyperbole.

MD: Right.

RR: And the untold damage and influence these people have. And then Dirty Suits – the funny thing is, the lyrics are now nine years old, but they apply to today’s politicians if you think about it. We released that single by accident. It got released the day Donald Trump was elected and these words are still very pertinent in these matters.

MD: And how much interaction do you have on a regular basis with bankers and politicians?

RR: Well I have to withdraw my cash from a machine. And every month they take money out of your account.

MD: That’s true.

RR: Without telling you. So, I’m on a small budget and it’s takes… the money could go to better use, really.

MD: I’m sure it could. Well, they need it. You know we’ve got to keep the bankers fed and watered.

RR: If you go to their branch there, any service that they provide, they charge you five dollars.

MD: That’s true. They don’t do anything for free, that’s a fact.

RR: Then we go to Gandhi…

https://hallelujahpicassos.bandcamp.com/track/ghandi-father-of-the-nation

MD: Now I notice one thing on your song titles, a lot of them have parentheses and little additions to them. So how does that happen?

RR: Well, in the band we have two kinds of thinking. One wants the title to be exactly the same as the chorus. Say for instance with Salvadore, there’s lots of ‘miles away’. So, some people say we should use ‘miles away’ so people can identify with it. But then I am in the camp here, let’s call it Salvadore.

MD: So these are titles by committee.

RR: Yeah. Sometimes. Not all the time. So that’s what happened in the case of Salvadore (Miles Away). We compromised.

MD: Right. So now we’ve got Gandhi (Father of the Nation).

RR: And that is one I always wanted to do because in the nineties, when we were performing, I looked very much like Gandhi. Had had the glasses and the whole thing but a leather jacket. Subsequently, I met another performer called Aki who was from Fun-da-mental and when they came over here – he’s Pakistani – when he met me, he called me “Mad Max Gandhi” because I had biker boots and a leather jacket.

But the reason why this came about was because I created a mantra, Mahatma Gandhi Mahatma Gandhi. If you repeated it as a mantra it has a certain rhythm to it. Then subsequently I found five phrases that in general associated with Gandhi, from the history books. And then we slotted them in, and they all come from the autobiography of Louis Fisher. Even the quotes before, by Einstein, that’s read by Johnny Pain. And the quotes after, by General MacArthur, also from the book by Louis Fisher.

And it’s quite a simple exercise in mantra.

MD: Setting aside the fact that you and Gandhi resemble each other, is he someone you look up to?

RR: Of course! Non-violent resistance, we’re talking about civil disobedience, all those phrases that Gandhi… I mention the superficial stuff about me looking like him, but those things do mean a lot to me. And that’s one of the reasons we chose it.

MD: And I should point out, that it’s obvious listening to the music that you guys are still heavily into the whole Dub kind of sound and vibe.

RR: I think that’s more by accident. Maybe you’re right, because we’ve been living so long with it, with the genre itself. None of us hate it. We are very familiar with it, you know. But then the subject did come up that we try to expand on it a bit further and move out into different areas where one would introduce techniques into songs that you wouldn’t normally – and they were Dub techniques.

MD: So I wanted to ask you, like how-what the process is of actually putting some of these tracks together.

RR: Well, so if I write the songs, they start off with the lyric, melody. And then I usually have a sketch of an idea of how it works. And then the others listen to the brief I give them and from there it’s free-style. What needs to be done, how to convey the idea we are trying to convey to the listener. How heavy it should be, how hard – that sort of stuff.

MD: So you’ve got a pretty good idea going in what you think it should be…

RR: Yeah. And it’s not an autocracy. The others write tunes as well and then I will write lyrics for them as well. But I tried to be as varied as possible in the approaches. At the end of the album, for instance, I got given a computer tablet. I was stoked with this. What I didn’t realise was that you could download free music apps. Now I thought to myself that if I had that during the making of this album, there would have been a lot more digital noises on it. I would have really liked that.

MD: Well, there’s the next record.

RR: There’s the next record – absolutely. I’m hopefully optimistic.

MD: Now “Black Spade Picasso Core” you mentioned, has a past to it.

RR: Yeah. So “Black Spade Picasso” is our flag song and we always finish it and that’s the song we finish with, you know. Back when we wrote it, it was one of our first exercises in writing. And I knew you could be creative with it. And it’s based on a Peter Bruegel painting, “The 25 Proverbs.” And in the painting, you see the proverbs played out by different characters. So “Black Spade Picasso,” each line are those characters. So, the song is the painting and each line refers to a different situation. It was that approach. And it’s basically, if I may be so blunt, it’s about a pissed off immigrant, who had been living in New Zealand for about six or seven years. And this was the end of the 80s.

MD: What was the experience like for you? You must have come here in the middle of the 80s?

RR: 82 I arrived, at the age of 17, I might add.

MD: Because the country, I get the feeling, I’ve only been here since 94, but I get the feeling – I know it’s changed a lot even from there, so it must have been very different for you.

RR: Yeah, it was different. So, this song is my discomfort with the situation and my rage. Also, when in the conversation, references… European references or general references that people knew in general, but if I had to make an argument, I had to translate the argument – so I had to think of an argument, then translate it – so I had to do two things at once. And what happens then is you get stumped and stilted. And then people think you are a dolt, you know? And a lot of the immigrant people I talk to, of course they can’t express themselves. A lot of people think they are idiots.

MD: It’s hugely frustrating.

RR: Like I work with a Chinese mathematician in this cafe. Of course, he couldn’t speak English – his English wasn’t competent enough to teach. But this guy wasn’t allowed to teach, but I knew this guy was a mathematician, a professor no less. So hugely frustrating.

And the remnants of those people who thought I was a dolt and you know I didn’t help myself by dressing in the leather jacket, because in New Zealand they thing you are tavi and that sort of thing. I had nothing to do with that, it just was a pleasing aesthetic for me. Simple as that. But that is difficult because people talk to you differently.

So “Black Spade Picasso” is my anger and frustration in this culture. That’s what it is about.

MD: So we go from that, we flip the record over, and we’re “Happy Smile.”

RR: Right – we’re “Happy Smile.” Okay, now I mentioned Peter Bruegel again, so this is also about – funnily, it’s 25 years difference between So “Black Spade Picasso” and “Happy Smile” and “Happy Smile” is also about a Peter Bruegel painting. And it’s his peasant style. In it, you see the peasants – the reason I find the paining important is because back in those days, most painters got paid by royals, painted royals. They painted either biblical characters or Greek mythology. Bruegel paints ordinary people in villages. This song is from the perspective of the villagers. The people in the song, as they dance, they sing this song. That is how it came about. The lyrics are naive. I had to add “Naïve In Joy” just in case some people thought my writing skills weren’t up to scratch. So I edited it. I know the lyrics are naive, but that’s what it’s supposed to be.

MD: All righty.

RR: So “Gimme Heat” then, which is the second one…

https://hallelujahpicassos.bandcamp.com/track/gimme-heat-musings-of-an-autocrat

MD: …which is ‘musings of an autocrat’

RR: So this is one Darryn and Peter came up with. Darryn is playing guitar and it’s a funky type thing. At first, I didn’t know what to do with it. In the end, I came up with some lyrics and it’s from the point of view of an autocrat or dictator, potentate, hegemon, that sort of thing. And it’s him sitting in the chair thinking out loud. And his ego attached, and sex comes into it – power and sex, all these things that come into play. That’s what it is about.

MD: Sounds fairly relevant to what’s going on these days. Some things never change.

RR: Yeah. “Bullet Chant.” Now that is an exercise in klang association. Because English is a second language, I notice that, weekend – Saturday and Sunday – and ‘we can’ – like ‘we are able’… and a small can – I can make all those three sound the same. And that’s called Klang Association.

https://hallelujahpicassos.bandcamp.com/track/bullet-chant

MD: Ahhhh… OK That’s good to know.

RR: And it’s all play on words I use. I go from piquant (as in spicy) to a picanto. Canto is a song, a religious song, so it’s a play on words as well. So, the whole song is an exercise in that. And canto, also has a reference as well to a dirty word as well.

MD: Laughs – that’s what I was thinking first time I heard it.

RR: Yeah and there’s the “c” work in there… and there’s an ‘o’ on the end. So it works on all those levels as well. But that’s what Klang Association is. They have the same sounds. In English you call them homophones.

MD: Right. “Welcome Mat for a Stranger” is the next

https://hallelujahpicassos.bandcamp.com/track/welcome-mat-for-a-stranger

RR: So I wrote these words a few years ago, two years ago, maybe a year and a half. This was before the Christchurch incident. But this is about immigration, you know? I am an immigrant even after living here 35 years, because I present as different. And when I open my mouth, I am different and people will pick it up. And you see people’s attitude change. Some people positive, some people negative, depending on the answer I give… but the answer to their question is usually longer than their attention span.

MD: Right.

RR: They ask me where I’m from – I go Dutch – and I confuse them. But how come the colour of your skin? And then I go, well the Dutch, just like the English had colonies. And one of the colonies was Surinam. There were sugar plantations. So when slavery ended in the 19th century – the period from 1800 to 1900, they needed cheap labour. And next to Surinam, Dutch Guiana is British Guiana. So, the Dutch government asked the British if they could get some of their indentured labourers. And they were Indians. And how the Dutch imported a whole bunch of Indian from Beha and Mapadesh. And that’s my ancestry, so my great great grandparents were from there. And then my father immigrated from Surinam in the 50s to home. And then he gets killed before I was born, was murdered before I was born. So, I explain to you…

MD: I can see where, if you’re in a coffee shop somewhere and somebody asks you where you’re from, they could probably fade off before you get all that in.

RR: Yeah, exactly. But the thing is, I am culturally, socially, I’m Dutch. That’s how I was brought up.

MD: That’s interesting. People seem obsessed with finding out where somebody is from. Believe it or not, I have the same problem. It’s not as big a problem as I don’t really care that much, but people are always asking me where I am from. They assume I’m American, which I mostly am. But I was born in England and to be perfectly honest, I don’t care where I’m from, it doesn’t make that much difference to me. But people make all these assumptions. And I’m just a white, English-speaking guy. When you’re not even that close to being what they think is ‘normal’ then all bets are off.

RR: It has to be binary. Automatically with your accent, you have to be American – otherwise it doesn’t compute. The switches are turned the other way. Now we live in a complicated world.

MD: And I can understand how people are interested. They’re asking out of possibly very good motives, but still, it not…

RR: But you can be surprised. People ask, they’re interested. But I have found you are being judged at the same time. Let’s not make any bones about it.

MD: That’s true – absolutely right.

RR: And that’s where “Welcome Mat for a Stranger” is for – the hypocrisy of it all. They welcome you with your right hand, shake it – push you with the left at the same time. That’s how I felt, even after all these years. So, it’s only in the last fifteen years that I mention to people my Indian heritage and for some people it doesn’t matter, but people see you in a different light when you mention it to people.

And if it’s in the media, if Indian people are in the media – you see it automatically on the street if it’s a negative connotation, they react straight away. They associate it with what they’ve seen on TV.

MD: Right. I guess that’s why it’s so important – you hear people in Hollywood complaining about actors getting stereotypical roles and you think, ‘at least you got a job, what are you complaining about?’ but it really does have an effect on how the wider population sees that kind of person, for want of better terminology and immediately associate that with that because it’s all they know and that’s all they’ve seen over and over again.

RR: And if I grow a beard, then I’m Muslim. You stand at a bus stop and you hear these kids talking, ‘what is he, what is he?’ and people are discussing it. White old ladies give you wide berth, for instance. Or you walk on the bus and sit down and the lady in front of me pulls her bag closer. The lady beside me, in the aisle, pulls her bag closer. So, it is real. It is real.

MD: OK. “Fire Sandpaper Face.”

https://hallelujahpicassos.bandcamp.com/track/fire-sandpaper-face-2

RR: So this is a song that came to me – we all have certain cultural imprints from our childhood. So, this is a song about Franz Xaver Messerschmidt. He was a sculptor and he had these amazing faces. I remember them from my youth and recently, a couple of years ago, I saw them again on the internet and I went ‘click!’ It triggered something in me and I decided to write some lyrics about them. And that’s what Fire Sandpaper is about – the sculptures.

MD: Is he related to the guy…

RR: With the same name – I didn’t go that far. He was in the late 18th century. I didn’t go with his family tree afterwards.

MD: And then the album wraps up with “Voices of One.”

https://hallelujahpicassos.bandcamp.com/track/voices-of-one

RR: And this song is very close to my heart because this is about homeless people. I frequently play in the library and next door is the St Joseph Boarding House. That recently got closed. And they’re now making apartments in it. But these people were given notice. And you should see the anxiety these people had. It was because it was the last place they could go to. They didn’t know where to turn to. We’re talking about men in their forties and fifties, so they’ve been through the system, disillusioned, they don’t know who to trust. They lost contact with people. They’re not after help. They were anxious about losing their place to live. And subsequently I’ve seen a couple of them afterwards, 3-4-5 months living on the street, sleeping rough in the bushes, stuff like that. It is really harrowing to see. The only thing I had to give them was the number of the Auckland Action Against Poverty people. Maybe they could help. Maybe they had resources. The only thing I had to give them. It’s harrowing when you understand it. So, Voice Of One is about homeless people, and most of these songs are based on gospel hymns, songs, mantras and the religious experience – secular religious experience.

MD: So it sounds like the Hallelujah Picassos is a very different band now than it was in the early 90s.

RR: We are 25 years older. And I have no problem with growing old. We should present ourselves differently, more insightful perhaps. We’ve all experienced stuff. I’m not sentimental about the past. I do not want to relive my teenage years at all. And if I can write something in a way that people listen to, that’s what this record is about.

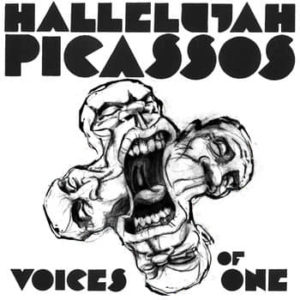

MD: What can you tell me about the cover?

RR: yeah – they’re big and huge.

MD: I’m thrilled that you came up here to tell me about this. This is great. You’ll have to let me know when you’re playing out again. We’ll get the word out and tell everybody about it. And we look forward to the next album.

RR: Thanks.

- VÏKAE – Tы мой океан (You’re My Ocean): 13th Floor New Song Of The Day - July 27, 2024

- Tami Neilson Announces “Neilson Sings Nelson” Tour - July 26, 2024

- R.I.P. John Mayall: British Blues Pioneer Age 90 - July 24, 2024

June 28, 2019 @ 10:19 am

I Used to Love Seeing Hp’s at the Gluepot. back in the Day of The Gluepot.Bobbylon on Drums. the Reggae/Punk/ Ska Sound love it.

June 30, 2019 @ 7:20 pm

Brilliant array of music then, I also enjoyed their gigs at De Bretts house bar.