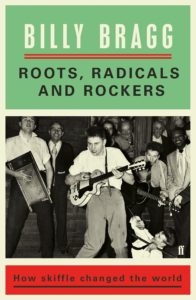

Roots, Radicals and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World – Billy Bragg (Faber)

Roots, Radicals and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World – by Billy Bragg / Faber and Faber $45

Told with joyous vigour, this book tells the story of jazz pilgrims and blues blowers, Teddy Boys and beatnik girls, coffee-bar bohemians and refugees from the McCarthy witch-hunts. Billy Bragg traces how the guitar came to the forefront of music in the UK and led directly to the British Invasion of the US charts in the 1960s.

This is quite possibly the first book to ‘properly’ explore the short-lived Skiffle phenomenon in any really depth. On the surface, it’s a musical style that could easily be brushed aside as a  post war hillbilly revival – A last gasp for Britain’s vaudeville performers whose careers have been swept aside by the tidal wave of Swing, Big Band Music and Jazz brought to UK by American troops stationed there during the war. On the other hand, author and musician Stephen William “Billy” Bragg argues skiffle was the first and possibly the best example of British youth’s DIY ‘punk’ attitude which sparked a revolution that shaped pop music as we have come to know it.

post war hillbilly revival – A last gasp for Britain’s vaudeville performers whose careers have been swept aside by the tidal wave of Swing, Big Band Music and Jazz brought to UK by American troops stationed there during the war. On the other hand, author and musician Stephen William “Billy” Bragg argues skiffle was the first and possibly the best example of British youth’s DIY ‘punk’ attitude which sparked a revolution that shaped pop music as we have come to know it.

It’s no surprise that Bragg chose this topic because for nearly his entire 30-year recording career he’s been involved at the grassroots of political and social movements. As he’s told the UK press on multiple occasions: “I don’t mind being labelled a political songwriter. The thing that troubles me is being dismissed as a political songwriter.” And even more than before, he’s still searching for a New England.

Skiffle, as a style, if that’s the right word, emerged from the trad-jazz clubs of the early ’50s. Initially it was another vehicle for novelty songs, skits and old time music hall – a tradition that British performers longed to revive but it’s simple style, often played on guitar, washboard, harmonica and piano meant that nearly anyone could pick up an instrument and play. So skiffle was adopted by kids who growing up during the dreary, post-war rationing years. These were Britain’s first teenagers, looking for a music of their own in a pop culture dominated by crooners and mediated by a stuffy BBC. With a reinvented version of a Leadbelly tune Lonnie Donegan hit the charts in 1956 with a version of Rock Island Line. And soon sales of guitars rocketed from 5,000 to 250,000 a year. It was that simplicity, Bragg argues, that likens the style to the punk rock that would flourish two decades later because, at the end of the day, skiffle was a do-it-yourself music.

Way back, before BREXIT, the country had another identity crisis. As Orwellian Britain was recovering it desperately needed some kind of release from the blandness and drudgeries of a post war concrete-grey world. Victory was not sweet. It was harsh. There were ration cards and shortages, laws and restrictions. America had exported its glamour to Britain but it was all still black in white in Old Blighty. And for the youth of the country, who’d grown up with the scars of the previous decades they were wanting to escape with nowhere to go. As Johnny Marr wrote in his own biography, his play ground was the rubble of a bombed-out Manchester. Not the glam of the Hollywood Hills.

The hit parade dominated by ‘Old Men’ – crooners and novelty songs. Music was for grown -ups. So it was refreshing when that was all disrupted not just by Lonnie Donegan’s Rock Island Line (1954) but by the equally homespun Don’t You Rock Me Daddy-O by the Vipers and the Chas McDevitt Skiffle Group’s Freight Train (feat. Nancy Whiskey). Skiffle was the natural replacement to the exotic Calypso styles. Although it drew its roots from Blues it was ideally suited to British working class accents and certainly struck the right chords with the audiences.

As far as Bragg is concerned Donegan is the hero of British skiffle but it all starts earlier with trumpet play Ken Colyer who boarded a ship in 1952 as a galley cook and landed in New Orleans. There he gigged with local musicians. Eventually he was kicked out of the USA, when his visa expired and for ‘consorting’ with black musicians, he set up shop in London with his own new sextet playing New Orleans-style jazz, with Chris Barber on trombone and Donegan on banjo. Colyer also played guitar with a subset of the band – including his brother, Bill, on washboard – performed interval sets featuring folk, blues and country songs. Ironically Colyer and his brother were eventually sacked from their own ensemble. Re-labelled the Chris Barber Jazz Band the group recorded their first album in the summer of 1954, including the add-on Rock Island Line by the great blues singer Huddie Ledbetter (Lead Belly). The record company pretty much ignored this tune for over a year until finally released, almost by accident. And the rest is history.

For players, the appeal of skiffle was immediate. All it took to create an approximation of the sound heard on a song like, say Rock Island Line was a bass made from a tea chest and a broom handle; a zinc washboard and a set of metal thimbles; and a guitar, uke or piano. Someone also had to sing, of course, roughly in the southern blues and country styles. Because there was no amplification rehearsals could go ahead in front rooms of terrace houses without annoying the neighbours. Because it was a cheap and easy music to learn and play, guitar sales soared. On a different level this was the parlour music that was once a vital part of British social graces, but perhaps more lively.

Overall, Bragg acknowledges, the significance of skiffle is subject of heated debate. For our hero, Lonnie Donegan, it probably became an albatross as much as an eagle’s wings. It took him from obscurity to fame. He didn’t do himself any favours, though. Recording tunes like My Old Man’s a Dustman and Does Your Chewing Gum Lose Its Flavour On The Bedpost Overnight? relegated skiffle back down to the ranks of novelty music. Although many bands and performers chose to return to the style later on. Paul McCartney and John Lennon returned to their roots and borrowed heavily – You can hear it on When I’m 64 and Rocky Racoon, for instance.

Bragg rounds off his book with a kind of Post-skiffle chapter, bringing the connections of Led Zeppelin, Van Morrison, The Who, The Bee Gees, all who owe their careers to their early interest in skiffle and it’s motivations to get them playing. He then leaps ahead to remind us that the Sex Pistols, The Clash, The Damned and many others of the 70’s all played London’s 100 Club in 1976 with the same brazen attitude to “set out to democratise popular culture”.

Skiffle was a working-class music at best and even could be egalitarian at times, especially when the BBC got hold of it. Many of Britain’s best rock musicians came from the streets. You can see how Bragg makes the connection. Not bad for a working-class kid who failed his 11-plus and missed out on a place in University. His work, life and now this book speak volumes more than any professor, and with more colour and relevance than some tedious talk in a dusty lecture.

Tim Gruar

Roots, Radicals and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World by Billy Bragg is available through Faber for $45.

- VÏKAE – Tы мой океан (You’re My Ocean): 13th Floor New Song Of The Day - July 27, 2024

- Tami Neilson Announces “Neilson Sings Nelson” Tour - July 26, 2024

- R.I.P. John Mayall: British Blues Pioneer Age 90 - July 24, 2024