The Zone of Interest – Dir: Jonathan Glazer (Film Review)

The Zone Of Interest is the Oscar nominated Holocaust Film from master filmmaker Jonathan Glazer that is daring but ultimately underwhelming.

Starring: Sandra Hüller (Anatomy Of A Fall), Christian Friedel & Ralph Herforth.

It is impossible to create imagery that reflects the atrocities of the Holocaust. Yet, this history must be told. This paradox, which cinema has wrestled with, has given us films like Night & Fog and Shoah that deal with the collective memory of the Holocaust. These films suggest that you should not and cannot depict this atrocity as you cannot provide an image of the unimaginable. In contrast, films like Schindler’s List, The Pianist and The Counterfeiters and their mode of representation insist that to see is to believe. The historical content in these films is dubious, as Hollywood and ‘artistic license’ allow the Holocaust to be trivialised, fictionalised and fetishised. A counter to this critique is that these films and their success prevent the disappearance of the Holocaust from Western cultural discourse and memory.

A film like The Boy in the Striped Pajamas was commonplace in high-school classrooms. In my Year 11 English class, a poster of the film was stapled onto a fraying thatched board. The film, often young adults’ first introduction to the Holocaust, is a powerful and affecting text, but historians have heavily criticised it as it “may fuel dangerous Holocaust fallacies.” Despite The Boy in the Striped Pajamas contribution to the problematic misconceptions of this atrocity, it remains a contested and potentially damaging educational resource.

A film like The Boy in the Striped Pajamas was commonplace in high-school classrooms. In my Year 11 English class, a poster of the film was stapled onto a fraying thatched board. The film, often young adults’ first introduction to the Holocaust, is a powerful and affecting text, but historians have heavily criticised it as it “may fuel dangerous Holocaust fallacies.” Despite The Boy in the Striped Pajamas contribution to the problematic misconceptions of this atrocity, it remains a contested and potentially damaging educational resource.

The Zone of Interest, like The Boy in the Striped Pajamas is based on a novel. This film is the first in a decade by British writer and director Jonathan Glazer. His previous outing, the haunting Under The Skin, is a modern masterpiece. The Zone of Interest doesn’t borrow much from the novel—the same name and perspective. The novel by Martin Amis features three narrators and a story structure that shifts between its protagonists. Glazer has scaled back and crystalised The Zone of Interest, taking inspiration from how Amis has depicted the interior life of Paul Doll, a fictionalised Rudolf Höss.

The Zone of Interest is set in Auschwitz in 1943. Höss was the longest-serving commandant of the concentration and extermination camp, which operated from May 1940 to January 1945, murdering at least 1.1 million people, mainly Jews. Höss, his wife, Hedwig, “the Queen of Auschwitz,” and their five children strive to live an idyllic life. The film opens and rests on a pitch-black screen. For a minute or so, you gradually submerge into hell as Mica Levi’s startling and sparse score oozes dread—a gargling siren song of death. Cut to white. The Höss family are frolicking in the river as the warm afternoon sun beams down on them.

A few scenes later, Rudolf Höss is now fishing. Birds chirp as his children play by the rocky riverside, splashing water onto each other. A turbid mass of grey water floats towards him. Höss examines the strange matter, his hand pulling out an object from the murky river. It’s a bone fragment presumably from one of the camp’s victims. This relationship between the blissful scenes of domestic pleasure and the horrors of the Holocaust is what Glazer is interested in exploring. Rather than asking how ordinary people could become such monsters, he asks, “How like them are we?”

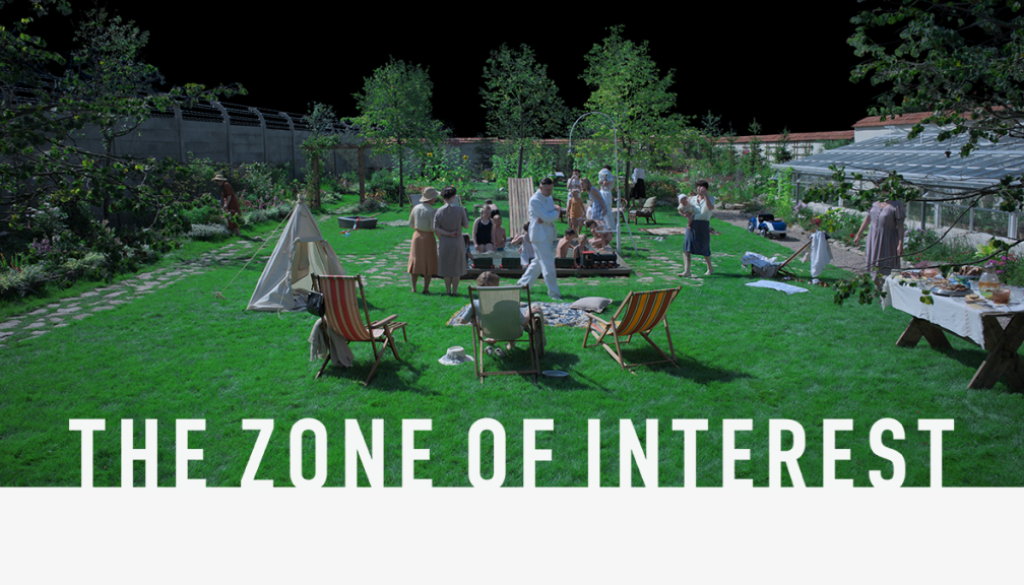

The Höss home, a two-story grey stucco villa, is nestled up against the walls of the camp. Chris Oddy, the production designer, spent several months converting a derelict home on location in Auschwitz into an exact replica of the Höss house. What is striking about the house in The Zone of Interest is its proximity to the camp itself. The guard tower and camp entrance can be seen from the dining room window. Prisoner blocks and a camp wall loom over luscious plots of vegetables, herbs and flowers. At night, the fires from the crematorium glow through bedroom windows, casting a sickly orange shadow over silk sheets.

The formal decision by Glazer not to depict the atrocities happening within the camp means he leans on sound designer Johnnie Burn to build a soundscape of death. It is a bold conceptual innovation for Glazer to conceive The Zone of Interest as two films—there is the film you see (‘Film 1’) and the film you hear (‘Film 2’). The juxtaposition between the daily lives of the Höss family and the mass murder they are choosing not to hear is chilling. This cognitive dissonance allows them to go about their lives strolling in the garden or gossiping over coffee as the machinery of death constantly rumbles. Based on a 600-page research document compiled by Burn, the soundscape juxtaposes their ‘ordinary’ lives with incessant gunshots, dog barks, blood-curdling screams, and chugging steam trains. In The Zone of Interest, we hear what the Höss family chooses to ignore, but as a viewer, you must become complicit and tune out the camp’s noises. Otherwise, the conversations we overhear that describe new crematoriums or the kohlrabi, which the Höss children love to eat, are muffled by this sinister soundscape.

With cinematographer Łukasz Żal, Glazer embedded multiple cameras in and around the house. This approach, which he has dubbed “Big Brother in the Nazi house”, is a panoptic surveillance system that makes The Zone of Interest more akin to a fly-on-the-wall style documentary. We are voyeurs to the Höss’s and their comfortable family life. Moreover, without artificial lighting, only practical or natural lighting, each domestic vignette is flat, strange and ugly. The blossoming garden is grotesque, not a garden of Eden, but a site of darkness and despair. Each interior scene is unsightly, a horror film that is only heard. There are no jump scares or evil villains. Höss is a dull bureaucrat who’s good at his job. Can one do evil without being evil? The Zone of Interest is an uncomfortable reminder that we are not so far removed from Höss and his family as we assume.

With The Zone of Interest being such a singular text in its conceptualisation of what a Holocaust film looks like, it’s frustrating to recognise its failings. The film has traded the trappings of a period museum film for a series of art-house clichés. Glazer is obsessed with the poetics of slow cinema; scenes linger as he attempts to wring meaning from each idle pixel. The film bizarrely switches to a fairy tale type sequence with night-vision thermal images, and yes, there is a ‘point’ to it. It feels bizarre however. The world is not without morality, we know that. Later in The Zone of Interest we observe Hedwig walking the manicured garden with her mother. The film cuts to focus on her flowers, nourished by the ashes of the dead. The Zone of Interest then fades to a blood-red screen. This edit should be a monumental moment, but it is too overt. The point has already been made about how beauty and horror can exist side by side. Only the naïve think the two ideals exist in a vacuum, separate from each other.

I commend Glazer’s willingness to experiment with the medium, but this stylistic bravado is more kitsch than genius. The film is so deliberate with its clear and obvious subversions of Holocaust cinema that it becomes tedious. The Zone of Interest isn’t nearly as thought-provoking as it thinks it is. Little room is left for discovery. As The Zone of Interest cuts to a pinhole of light, we are allowed to look away from what the film demands we observe. Instead of being a reflexive critique of complicity and ethical complications of representing the Holocaust, Glazer loses his nerve. He hides behind a veneer of intellectualism rather than attempting to peer through the darkness.

Thomas Giblin

- VÏKAE – Tы мой океан (You’re My Ocean): 13th Floor New Song Of The Day - July 27, 2024

- Tami Neilson Announces “Neilson Sings Nelson” Tour - July 26, 2024

- R.I.P. John Mayall: British Blues Pioneer Age 90 - July 24, 2024